“He was excited. Excited and happy, like a dog which has followed a cold trail for a long time, and suddenly finds it a hot one.”

Nurse Detective Hilda Adams about Inspector Patton 68

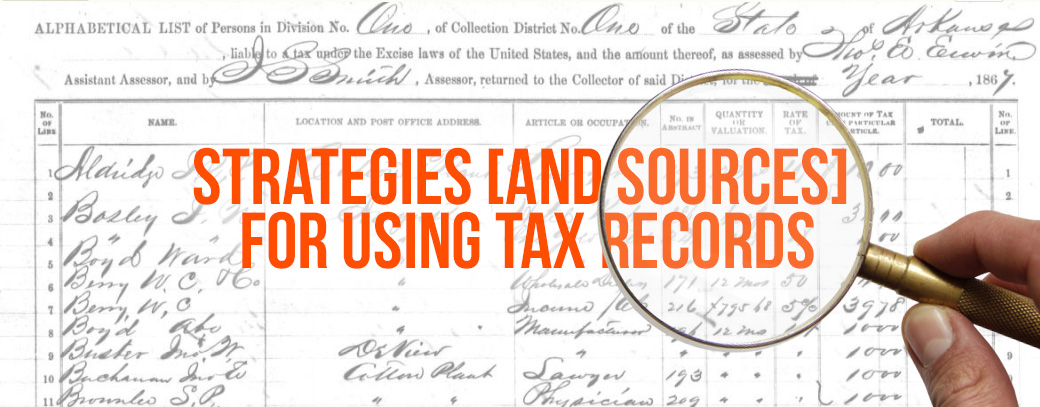

Research in tax records has produced this reaction of excitement for many genealogists and has resulted in many “hot trails.” A number of states and towns have preserved tax records that date to their early years; others have not been so diligent. Nevertheless, the genealogist needs to use them whenever they exist. They are particularly valuable for research in Georgia, Kentucky, North Carolina, Virginia, and early West Virginia when it was part of Virginia. The surviving records are usually found in county courthouses or in state archives. Many have been microfilmed and are available from the Family History Library.

Tax records are kin to land records because residents paid taxes on land they owned, as well as on slaves, horses, cattle, oxen, personal property, and luxury items such as clocks and carriages. In some cases, specific items were taxed in a given year, such as certain items of furniture, mirrors, and window curtains in Virginia in 1815. Sometimes, as in Virginia, the land tax records and personal property tax records are separate. People who owned no land could still have paid poll taxes (head taxes) on themselves, slaves, or sons of taxable age. Widows were not normally taxed except on their land and slaves, although men of taxable age in their households were taxed.

Following the existing tax rolls for a given ancestor over a period of years can give the researcher quite a bit of information. Yet, each state had its own laws, forms, and lists of taxable property. Free men could begin being taxed when they became 16 or 18 or 21 years old, depending on the state and the time period. Slaves were often classified in the tax rolls in age groups, such as those under 12, 12 to 16, over 16, or 16 to 55. These categories also varied from place to place and year to year. Usually, the tax laws designated an age after which a person was exempt from certain taxes.

Information Sometimes Found in Tax Records:

What kind of information, in general, may be shown in these records? Below are some of the standard column headings, but these vary from state to state, even from year to year:

- Name of the person charged with the tax, usually the head of household

- Names of free men of color being taxed

- Number, and sometimes names, of taxable free white males in the household

- Number of acres of land owned, sometimes with location information–adjoining neighbors, watercourse, distance from the courthouse, or district number

- Name of original grantee of land

- Number of slaves in the household each year, sometimes with their names

- Rent received on rented property

- Number of horses, oxen, or cattle owned

- Value of land, slaves, or other taxable property

- Amount of tax paid

What other information might the genealogist glean from studying some tax rolls?

- Relationships, either expressed, deduced, or suggested

- Suggestions of birth order among sons in a family, depending on when they first were named or became a head of household

- Suggestions of death year or moving, when someone no longer was listed, when an estate was listed, when someone was named as guardian of the children or administrator of an estate, or when someone is taxed for the property formerly belonging to another person

- Occupations, expressed or implied by paying license fee

- Suggestions of family groups of slaves, when, over the years, the same slaves were named in a household; sometimes, slaves’ ages

- Changes in a person’s net worth or lifestyle, expressed in changes in the number of slaves, livestock, and luxury items

- Preliminary identification of neighbors by studying adjoining landowners and watercourses, or when the tax collector dated each entry and it appears that he visited the households in person. [END]

The foregoing article was excerpted from our recent reprint of Emily Anne Croom’s excellent manual, The Sleuth Book for Genealogists: Strategies for More Successful Family History Research. The Sleuth Book is brimming with wonderful checklists, case studies, and novel approaches for using any number of genealogical source records. For more information about this research guide, please click the following button: