New York Researchers’ New Resource

Any researcher who works with he records of turn-of-the-18th-century New York should be delighted to learn about the following new research aid: New York in 1698: A Comprehensive List of Residents, Based on Census, Tax, and Other Lists, by Kory L. Meyerink. Genealogist Meyerink spent over two decades piecing together a comprehensive census of the inhabitants of the New York Colony in 1698. There is no other publication for this period like it. Please read on for details.

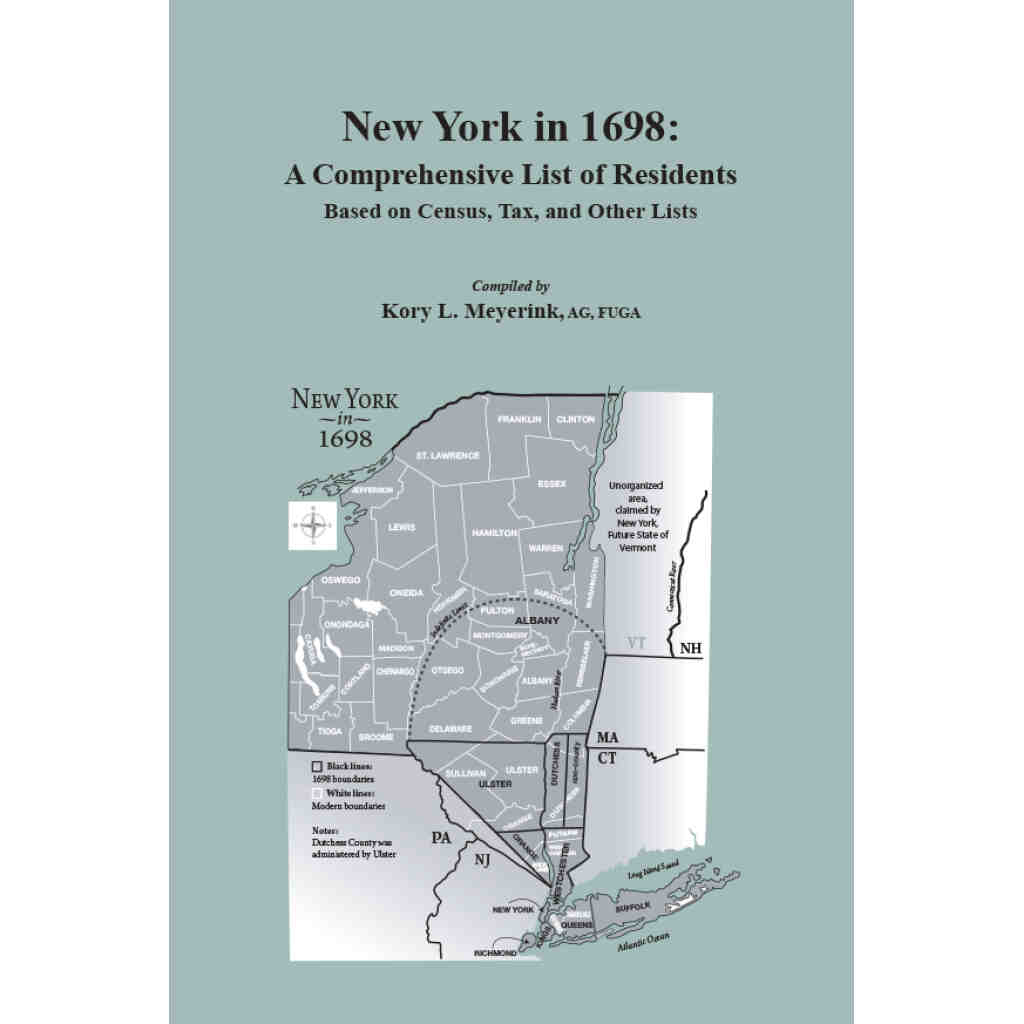

New York in 1698:

A Comprehensive List of Residents, Based on Census, Tax, and Other Lists

by Kory L. Meyerink

On or about May 3, 1697, Governor Fletcher of New York authorized an every-person census of the colony. Fletcher’s order was widely ignored, but his successor, Governor Bellomont, succeeded in carrying out the order and all the returns were submitted by the Fall of 1698. The various county totals appear in Bellomont’s report to the King’s Council of Trade and Plantations in November 1698. Many of the enumerators did, in fact, record the names and vital information of all inhabitants under their purview; others recorded only the heads of household, adding the numbers of other persons at each dwelling. Although the surviving manuscripts of the census were lost in the 1911 fire at the state archives in Albany, about half of the returns survived in the form of handwritten copies or published articles, several appearing in the New York Genealogical and Biographical Record.

The work at hand is the result of a 26-year, masterful reconstruction of the 1698 census of New York by the esteemed genealogist and librarian Kory Meyerink. In this effort, Mr. Meyerink was aided by not only the “surviving” portions of the 1698 census but also the statistical summaries of the census which have survived the passage of time. The fact is that we know exactly how many men, women, and children (all free whites) and slaves (usually black, and sometimes Native Americans) were counted in the census. With these numbers in hand, Mr. Meyerink was able to locate more or less contemporary substitute sources (e.g., militia lists, tax lists, church records, town minutes, etc.) and reconstruct the residents of the missing counties, towns, and manors. In a number of cases, he was able to find the names of the same New Yorkers on multiple lists, thereby enhancing the accuracy of the reconstruction. In other cases, he assembled lists as “composites,” from multiple sources (e.g., Easthampton, Rye, etc.). In all, he has identified by name 96% of the men, 50% of the women, and at least 40% of the children alive in the colony of New York in 1698.

New York in 1698 is arranged alphabetically by county and thereunder by town, ward, or manor. The author begins each county chapter with a detailed discussion of the reconstruction variables: original source(s), spelling, layout of the original information, statistical recap, a brief history of the area under investigation at the time of the census, and a bibliography for further research on that county. The chapter-by-chapter lists of persons are arranged to conform to the earliest known transcription of the 1698 census, or substitute. The volume concludes with a complete 13,700 name index and, owing to the significant New Netherland heritage of turn-of-the-17th century New York, a substantial listing of Dutch names with their English versions. Mr. Meyerink’s historical and methodological Introduction to the book–which also contains a separate bibliography–not only provides insight into the “missing” census itself but also is must reading for any genealogist or historian planning to conduct research into this fascinating period.

Recent Blog Posts