Transferring Land from Government to Individuals: Model Two: The Colonial Government System

By Patricia Law Hatcher

In the April 7 issue of “Genealogy Pointers,” we introduced the first of the various systems by which land was transferred by one of the colonial monarchs to individuals, The New England Model. As Patricia Law Hatcher explains in her definitive study of U.S. land records, first transfer varied both geographically and chronologically throughout the British colonies. This second installment of the land transfer process describes the Colonial Government System of Land Transfer, which was practiced in the southern colonies and differed markedly from New England. The second model is reprinted verbatim below, from pp.70-73 of Pat Hatcher’s Locating Your Roots. Discovering Your Ancestors Using Land Records.

MODEL TWO: THE COLONIAL GOVERNMENT SYSTEM

In the royal colonies of the South, much of the land passed from the crown to the administration of the colony in a fairly straightforward manner. For example, once the crown decided in 1623 that the Virginia Company of London was not doing a good job of achieving the goals the crown desired–settling Virginia with the intent of returning valuable products to England–it revoked their charter and instituted a system with a royal governor, a model that would be followed in other areas.

Land Sales

All colonies and proprietors eventually offered land for sale. The rules and costs varied over time, influenced in part by competition from other areas. The price might include a cost per acre, an annual quitrent (a remnant of the European feudal system), up-front processing fees, or any combination thereof.

Most of these areas followed the indiscriminate survey system, meaning·that land was selected first and then it was surveyed. South Carolina and Georgia, however, both made some attempts at methodical surveys before offering land

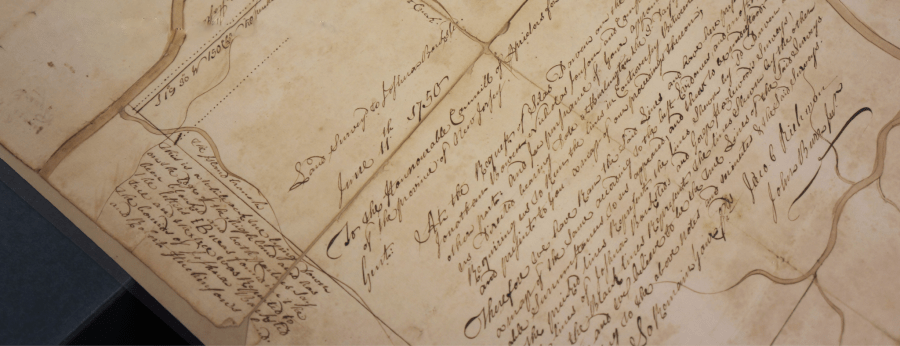

Grant Process

Grants or patents (the terms mean the same thing, but be sure to use the right term for your locality–Virginians are particularly touchy about this; they had patents during the colonial period and grants after, but the Northern Neck always had grants) had to be obtained from the capital. If buying from a proprietor, the man had to go to the office of the proprietor’s agent. Sometimes individuals hired agents or issued powers of attorney to avoid making the lengthy trip twice. Eventually in some areas, agents were established closer to where the new land was available.

In general, the process was that an individual first established his right to acquire a certain number of acres, either by headright (see ” Headrights” below) or purchase, and received a warrant. He stated exactly where the land was (in other words, it wasn’t an open warrant). His warrant was recorded so as to (theoretically) prevent overlaps.

The warrant allowed him to hire-at his own cost-a surveyor (usually there was a designated surveyor for an area).

Once he had the survey in hand, he could return to the capital and—after making any required adjustments in fee based on the dissimilarity between the acreage of the warrant and that of the survey-would mature the warrant into a grant (or patent). Warrants and even surveys were negotiable instruments that could be assigned to other individuals.

In general, then, the broad process for the first transfer to an individual outside of New England was:

1. obtain right

2. survey

3. grant

Headrights

Virginia, the proprietorship of Maryland, parts of the Carolinas, Georgia, and the Republic of Texas used a headright system to distribute land to promote immigration.

Records of headright claims often provide information quite different from records of simple land purchase. For example, the headright system in Virginia said that anyone settling in the colony had a right to fifty acres. In practice, the person paying the costs of transport usually was considered to own the headright. If a man brought his wife and two children, he was eligible for 200 acres. If a plantation owner imported seven servants, paying for their passage, he was eligible for 350 acres. If a ship captain imported men and women who were sold as indentured servants, he could claim their headright. As a ship captain, he probably didn’t want land and therefore sold the headright with the indenture or possibly to an individual who was buying up headrights.

Fifty acres wasn’t a practical amount in Virginia, so it appears there was a brisk trade in headrights, allowing larger grants to men who hadn’t participated personally in the importation. Other localities instituted restrictions, such as requiring claimants to appear personally and provide details, and there was less abuse of the system. North Carolina, for example, did not allow the sale of a headright until the person had been a resident for two years.

Headright claims may be found in court records or in land records. The Virginia patents, for example, give the names of the headright individuals and have now been published up to the Revolution. Thus, you can find the “immigrated by” date in land patents for a seventeenth-century Virginia ancestor who never owned land. There were, however, no records of immigration for the courts to compare to. Hence, there were many abuses, usually with individuals being claimed more than once.

Maryland found itself desperately needing settlers and instituted a headright system early. However, it failed to specify that the settler had to have come from England, thereby attracting some Virginia settlers (who might already have had a Virginia headright) into Maryland, especially on the eastern shore. The headright system operated only briefly in Maryland and the Carolinas, largely because of the abuses, and it died out in Virginia after the early 1700s. In spite of the earlier experiences, Georgia used the system when it was seeking settlers.

Land Lotteries

To encourage settlement in the western and northern portions of the state, Georgia held a series of land lotteries in 1805, 1807, 1820, 1821, 1827, 1832 (Cherokee), 1832 (Gold), and 1833.

Each lottery created two lists–one of the eligible, one of the winners. However, eligibility lists do not survive for all counties for all lotteries. When they do, they can be very valuable. Consider the case of Lemuel E. Owen. He first appeared in Illinois on the 1820 census. In 1850 we learn that he was born about 1798 in Georgia.

Of all the land lotteries, that of 1807 had the most liberal terms. One draw was given to men over twenty-one, widowed or single women over twenty-one, a minor orphan with the father (or father and mother) dead, or to a family of orphans whose father was dead but whose mother was living. Two draws were given to a married man with a wife and at least one child, or to a family of orphans who had lost both parents. The only exclusions were for the winners of the 1805 drawing. Thus it is that I learned so much about Lemuel.

The eligibility list for Oglethorpe County survives and has been published. Carefully study any list. Do not just grab the information about your ancestor and ignore the rest. One portion of the list includes the following:

2 William Owen, Senior

[two names]

1 Milley Owen, Widow|

2 Lucy Owen, Lemuel Owen, Levie Owen, orphans of Obediah Owen, Deceased

1 Salley H. Owen, 21 years of age

The names are grouped together, strongly suggesting familial connections. Since Salley is listed immediately after the orphans, she might be their sister. However, she would have been born before about 1786, which makes quite a gap (Levi was born in Georgia in 1800, and Lucy married in 1813, suggesting a birth around 1792). Milley would seem to be a good candidate for the mother of the orphans of Obediah–except for the terms of the draw, which explicitly say that a family of orphans with the father dead but mother living only gets one draw.

The lists establish the name of the father of the three siblings and that Obediah died by 1807. Obediah does not appear on the 1790 tax list of Wilkes County (the parent of Oglethorpe), but he is there in 1794, with no land, but next to William Owen on Long Creek. The 1800 Georgia census survives only for Oglethorpe; Obediah and presumed wife are 26 to 45, and their presumed daughter is under 10, hence Salley H. is not another daughter. We have, however, four “families” here to help with our future research.

Continuing our study of the lotteries, we find that Lemuel Owen of Putnam County had a successful draw in the 1821 lottery for land in Fayette County. Is this my Lemuel? No. We must always analyze land records in context with other records. Lemuel may seem an unusual name to us, but it was annoyingly popular in this time period. My Lemuel, as mentioned previously, was already in Illinois by 1820. This Lemuel married in Putnam in 1815 and raised a family in Georgia.