New Pocket Guide a Great Source for 17th- and 18th-Century Irish Census Substitutes

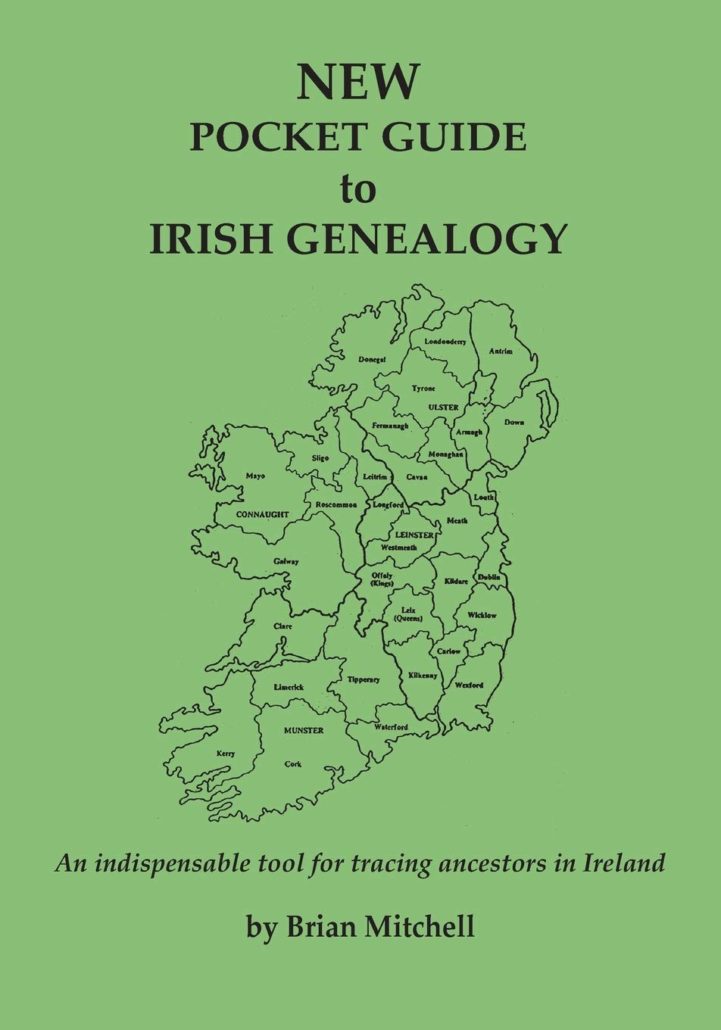

Brian Mitchell’s New Pocket Guide to Irish Genealogy is a wonderful combination of how-to book, guide to sources, and case studies–in only 120 pages. It’s expert genealogist Mitchell’s contention that the most important sources for Irish genealogy are the civil registers of births, marriages, and deaths; church registers of baptisms, marriages, and burials; gravestone inscriptions; wills; the 1901 and 1911 census returns; the mid-19th-century Griffith’s Valuation; and the early-19-century Tithe Applotment Books. Mr. Mitchell covers these sources in detail; however, he also provides excellent summaries of other useful Irish sources, such as census returns, military records, Ordnance Survey Memoirs, and many more. To illustrate what else you can expect to find in the New Pocket Guide to Irish Genealogy, following is a sample of the section Brian Mitchell devotes to Irish Census Substitutes.

17TH-AND 18TH– CENTURY CENSUS SUBSTITUTES

Flax Growers’ Lists

In 1796 lists were compiled by county and parish of farmers who were entitled to a grant for sowing flax seed. The grant was to be in the form of equipment used in the linen industry.

In the 18th and 19th centuries, flax was one of Ireland’s chief crops. Although linen production accounted for almost half of Ireland’s exports, it was very much a cottage industry. Flax was grown on very small farms, prepared and spun into linen yarn and woven into webs of cloth by families in their own homes, and sold in linen markets in towns to the linen drapers and bleachers who finished the linens for sale or export.

However, as people were more interested in spinning and weaving than cultivation, the Irish Linen Board came up with a plan in 1796 to encourage farmers to grow more flax seed. Free spinning wheels or looms were to be granted to farmers who planted a certain acreage of their holding with flax. A quarter-acre of flax equaled one spinning wheel and those who grew over five acres or more received a loom. County inspectors were appointed to receive claims from the growers, and county lists, detailing the civil parish of residence (but not the townland address), were published as official documents of the Board.

The names of over 56,000 recipients of these awards have survived in printed form arranged by county and parish. The economy of Ulster, in particular, was tied to linen production. The northern counties of Tyrone and Donegal had the largest number of spinning wheels awarded. Ulster had 65% of the wheels, the remaining were distributed throughout Ireland with no records existing for Dublin and Wexford.

The only known surviving copy of the records is held at the Linen Hall Library of Belfast (https://linenhall.com). The Public Record Office of Northern Ireland holds a photocopy of the original volume. An online version of the Flax Growers’ List is free to search, either by county or by surname, at www.failteromhat.com/flax1796.php.

The Religious Census of 1766

In March 1766 the Irish Parliament authorized an all-Ireland religious census. Church of Ireland (Protestant) clergy in each parish were instructed to return a list of the families in their parishes, identifying whether they were Protestant or Catholic.

Unfortunately, none of the 1766 returns list all members of a household. An examination of the returns shows great variations in their usefulness. For example, the return for Cumber parish, County Derry merely gives a numerical breakdown of Protestants and Catholics in each of its constituent townlands. It, therefore, serves no purpose for the genealogist. The returns for Nantinan parish, County Limerick names all Protestant householders but doesn’t provide their townland address, while that for Artrea parish, County Tyrone lists against each townland the occupiers and their religion.

Most of the original returns were lost in the fire at the Public Record Office in 1922. However, transcripts do survive for many parishes, especially in counties Cork, Limerick, Londonderry, Louth, Tipperary, Tyrone, and Wicklow. The National Archives of Ireland has compiled a table that shows where to find surviving returns for the whole of Ireland; it can be viewed at www.nationalarchives.ie/PDF/ReligiousCensus.pdf.

Ancestry.com has indexed about 11,000 names taken from transcripts of 1766 census returns created by Tenison Groves. Nearly all the records relate to parishioners in Northern Ireland.

The Groves Manuscripts, at reference T808 in the Public Record Office of Northern Ireland, contains, in 27 boxes, around 20,000 copies of genealogical working papers, comprising testamentary papers, notes, abstracts, census substitutes including freeholder lists, Hearth Money Rolls, poll books, 1766 religious census and other material, dating from c. 1650-1900. It was compiled and copied by Tenison Groves, a professional genealogist and antiquarian who worked at the Public Record Office of Ireland in Dublin from around 1900 until after the Four Courts Fire of 1922. The great importance of this archive is that it contains extracts from documents which were destroyed in the Irish Civil War in 1922.

A partial index to 1766 census returns can also be searched at Public Record Office of Northern Ireland’s online archive at www.nidirect.gov.uk/information-and-services/search-archivesonline/name-search.

Continued . . .

Editor’s Note: The balance of this section covers the Protestant Householders’ Lists of 1740, Hearth Money Rolls, and Muster Rolls.