“Pennsylvania-German Records,” by Don Yoder

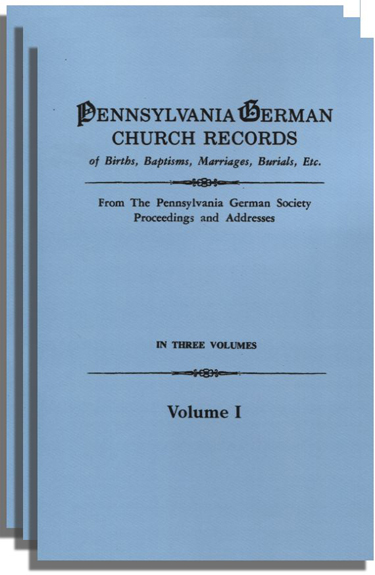

(The following article is excerpted from Professor Yoder’s Introduction to the three-volume collection, Pennsylvania German Church Records of Births, Marriages, Burials, Etc. From the Pennsylvania German Society Proceedings and Addresses )

We owe the translations of German church registers in these three volumes to the far-reaching historical and genealogical research program of the Pennsylvania German Society. The society was founded in 1891 by a group of Pennsylvanians interested in perpetuating the memory of emigrant forefathers and in studying the unique early American culture which has come to be known as “Pennsylvania German” or “Pennsylvania Dutch.”

The Pennsylvania Germans themselves are the descendants of emigrants from Europe in the seventeenth, eighteenth, and early nineteenth centuries. From 1683, when the first German settlement in the New World was planted at Germantown, through the late 1700s a varied procession of emigrants arrived from what is now West Germany, East Germany, Switzerland, and France (Alsace-Lorraine), with contingents of emigrants from Silesia (now in Poland) and Moravia (now in Czechoslovakia) and indirectly from Austria and other areas of Central Europe.

The Pennsylvania Germans were divided in religious adherence between the so-called “church people” (Kirchenleute) and the “sectarians” (Sektenleute). The former were comprised of the two major Protestant denominations from the continent of Europe, the Lutherans and the Reformed. The latter were made up of the Mennonites, the Amish, and the Brethren. A third category of religious adherence was the communitarian groups, represented by the Ephrata Society, the Moravian Brethren, and the Harmonites.

The records included in these volumes (see below) are those of selected Lutheran and Reformed congregations in colonial Pennsylvania, plus one Moravian record. All three of these groups kept excellent, careful registers of their. membership. Let us look at one of these churches, to see what types of help its records can offer to the genealogist.

St. Michael’s and Zion’s Lutheran congregation in the city of Philadelphia was the leading German Lutheran congregation in the Colonies, and its twin churches formed a kind of joint Lutheran cathedral. Its clergy were among the great spiritual and intellectual leaders of eighteenth-century America.

Among the first fruits of the genealogical program of the Pennsylvania German Society was the translation of the early records of St. Michael’s and Zion’s congregation, including baptisms, marriages, and burials beginning in 1745 and ending in 1762.

What is particularly valuable about these records is the great care with which they were kept by the early ministers. Sponsors at each baptism were carefully noted and illegitimate births were as fully reported as possible (important for genealogists!). In the marriage records, locations of the residence of bride and groom. if not from Philadelphia, were sometimes noted; the religion of the marriage partners, if not Lutheran, was mentioned; and the place where the wedding took place is noted, whether in the church in the presence of wedding guests, in the parsonage, or in private homes.

In addition to parishioners who lived in Philadelphia, the records include some persons from up in the country, or over the Delaware in New Jersey, particularly in the marriage record, since it was probably fashionable for country folk to cone to Philadelphia to get married and to honeymoon.

Among the illegitimate children listed were the offspring of temporary unions of German women with Irishmen, Englishmen, indentured servants, soldiers, and other putative fathers. If the parents married shortly before or soon after the birth of the child, the pastors charitably considered the births legitimate. And here at least the pastors did not, as was the case in some German records I have studied in Europe, pretentiously reverse the book and inscribe illegitimate births upside down.

Occupations are given too, in some cases. We read, for example, of Anthony Dashler the saddler, Jacob Roht the potter, Johan Christian Luprian the tailor, Johan Georg Ott the bookbinder, Johan Peter Buchner the locksmith, Tobias Bube the carpenter, and others.

In an age when confessional. lines were more precisely drawn, the pastors were careful to note non-Lutherans. For example, among the surprising number of Roman Catholics mentioned were Baltzer Smith, Diedrich Holtzhausin, Philip Eyler, Stephen Swermer, Anthony Ottman, Charles Alexander duBou (duBois?), Cathrina Spergler, Casper Kastner, Johann Paul Essling, Jurg Hirt, Niclas IIoltzlander, and Peter Walter. There are even a few Mennonites mentioned in the records, some free Negroes, and many “servants,” i.e., white indentured servants, whose masters’ permission was required when they married.

Occasionally the pastors noted down the European origins of their parishioners, often in the case of marriages, and even more so in the burial record. For example, in the family record of Wolfgang Unger and his wife, Anna Maria nee Zimmermann, the husband was from Flinspach in the Electoral Palatinate, beyond Heidelberg; the wife was from Nussloch near Heidelberg. On occasion a sponsor was listed from abroad, as in the case of the birth in 1747 of a son of Johann Heinrich Keppeles. The godfather was a man from Heilbronn in Wiirttemberg, whose place at the baptism was taken by a proxy. The Keppeles were among Philadelphia’s German merchant aristocracy, and Henrich Keppele was later to become the first president of the German Society of Pennsylvania, founded in 1764.

Among these notations of the European origins of the early members, there is a high proportion from Lutheran provinces of Germany such as Wurttenberg. The Philadelphia congregation appears also to have had a higher proportion of members from North Germany than some of the country churches. Examples from the baptismal record include Johan Just Bothmamn and Georg Wilhelm Rehburg from Hannover, Johan Thomas Koens from Hamburg, and Johan Peter Bogner (Buchner) from Braunschweig.

Of especial interest are the notations about the emigration of the parishioners. Several children were baptized with the note that they were born on the ocean. Sometimes parents of baptized children were described as “newcomers,” i.e., recently arrived immigrants. For example, in 1754, Magdalena Rohn was baptized, daughter of Henrich Rohn. The godfather was [Tans Ernst Mumbauer from Egypt (Northampton County). Both father and godfather arrived at Philadelphia on the Halifax, September 28, 1753.

Of the Reformed Church records in this work, those of the First Reformed Church in Lancaster begin in 1736. Like most of the Reformed congregations in colonial Pennsylvania, and to a certain extent all Pennsylvania German churches, the membership formed very much a potpourri of German regional backgrounds. There were, for example, Reformed families from the Palatinate and other Reformed provinces of Germany, including the pastors Hendel, Bohme, Faber, and Helfenstein, and such families as the Weidmanns, Trauts, Gensemers, Schreibers, and many others. There was also a large Swiss contingent, since the German-Swiss cantons of Bern. Zurich, and Basel were also Reformed. These Swiss families came to Pennsylvania either directly from Switzerland, or, more commonly, indirectly via the Pfalz or other areas in Germany; examples include the Dieffenderfer, Brunner, Buhler, Altdorfer, Schaffner, Rudisill, Stauffer, Dunkel, and Brenneman families. In addition, there were French-Swiss families like the Gallatins, and many Huguenot families from the Rhineland, including the Williars and Fortines (Fortineux) of Otterberg and adjoining parishes in the Palatinate; the Bushongs (Beauchamps), LeFebres, and others. From Hessen, Rheinhessen, etc., came the Bausmans, the Strenges (Christian Strenge, the Lancaster County fraktur artist), the Hurds, and others.

Pennsylvania’s Moravian tradition is represented in this work by Augustus Schultze’s “Guide to the Old Moravian Cemetery of Bethlehem, Pa, 1742-1910.” The Moravian Church, which was planted in America by Count Zinzendorf and his associates, was one of the most active of the spiritual forces in colonial Pennsylvania. The core of its membership had come from Czechoslovakia and Eastern Germany, but in Pennsylvania its converts included Englishmen, Danes, Norwegians, Swedes, and other Europeans, as well as converts from Pennsylvania’s Lutheran and Reformed churches, plus Negroes from Africa and the West Indies, and even American Indians. It was a cosmopolitan crowd indeed. Furthermore, the Moravians, because of their missionary drive, sailed back and forth from Europe to America, to the West Indies, Greenland, Guiana, and other mission stations, bringing new ideas and talents to the colonial scene.

The persons buried in the old “God’s Acre” at Bethlehem, on the quiet hill behind the church, represent this rich blend that was colonial Moravianism. An additional plus for genealogists is the fact that the Moravians, engaged as they were in heroic far-flung mission endeavors, made much of written biography; hence many colonial Moravians wrote spiritual autobiographies, giving the outward facts of their passage through life plus a careful recording of their inward progress in religion. It is these autobiographies, preserved by the thousands in the Moravian Archives in Bethlehem, that Dr. Schultze used in preparing the brief biographical sketches of those buried at Bethlehem. Particularly exciting for genealogists are the precise notations of the birthplaces of the European emigrants. And even in these short sketches one senses something of the excitement of belonging to the Moravian world in the heroic period of its missionary expansion.

Publisher’s Note:

Researchers can read the balance of Professor Yoder’s Introduction or search for their Pennsylvania German ancestors in the paperback edition of Pennsylvania German Church Records by ordering a copy from the following link:

- Pennsylvania German Church Records (Three-volume paperback set)

- Click here to see all of our Pennsylvania-German titles