Over the course of the last few months, we’ve published a number of excerpts from J. Michael Cleverley’s intriguing book, Family Stories . . . and How I found Mine. We’ve followed the Cleverley ancestors from the court of William the Conqueror, to the intrigues of the British nobility on the eve of the War of the Roses, to the exploits of Michael’s Rhode Island Revolutionary War ancestors, Nearly a century later we found them waging a struggling existence on a farm in Vernon County, Missouri, contending with disease, misfortune, and marauding bands on either side of the slavery issue. Today’s excerpt picks up Mr. Cleverley’s account in Nebraska in the year 1864, as his forebears take part in a wagon train headed for Utah, part of the “Mormon Pioneer” movement 70,000-people strong.

from “Promised Land”

The Great Plains

When the day to push off across the prairie came, everyone gathered around the wagons, children, men, women, the strong, the weak, the ill, and even those too weak or ill to travel. Tuesday, August 9, late in the afternoon, Howell whipped the reigns, the oxen trudged forward, and the wagon jerked to a start along the rutted meandering dirt trail. At first, they headed southwest to link up with the Nebraska City Cutoff Trail that eventually would follow along the south side of the Platte River. This was the first year Mormon trains used the cut-off that led to the Mormon Trail at Fort Kearny. Overall, it was an easier beginning with fewer difficult river and creek crossings than the trail further north (see Map H).

The Howards’ wagon was so full that they walked that day and every one after that. Thirteen-year old Mary Ann and their family friend, Mary Lowe, strode ahead of the wagon. Three-year old Tamar, sick and frail, travelled in the arms of her mother Ann. But they were finally moving along the last leg of their long passage, closer each day to the Zion of their dreams where two sons already awaited them.1

For many, the panorama of the prairie’s wide sweep, with its rolling hills and endless grass horizon, fashioned a stirring start for their journey. Sophia Goodridge wrote of the view in her diary, “…one endless sea of grass, wavy and rolling like the waves of the sea, and now and then a tree.” Another young woman felt incapable of adequately portraying her feelings, “Oh how I wish mine were a painters pencil or a poets pen.” She added, “My heart exclaimed how beautiful how wonderful thou art sweet earth.”2

But for the Howards, with a very sick child, weary from an already long journey, it was not so poetic. They still had two and a half months ahead of them, until late October, before the family’s journey would finally reach its end in Salt Lake City’s Pioneer Park.

The train only made about a mile before it stopped to sleep on a small creek surrounded with wood and grass. That night, at their first camp, two already enfeebled fellow travelers died. “We all felt very Sad they were buried,” wrote a young man sent from Utah to teamster emigrants west. The next day the company started off again after organizing a committee to look after the sick and bury the dead. The train only made about four miles this second day.3

Three-year old Tamar, suffering from what they called “Mountain Fever,” continued to weaken. By nighttime, her feeble body in her mother’s arms could last no more. It is hard to know what exactly it was, probably dysentery, diarrhea, and dehydration. They placed her small lifeless body into the ground. There was no coffin, little ceremony, just a shallow grave. They left Tamar there as the wagons pulled forward in their seemingly ceaseless procession. The rest of the family was distraught and distressed. The little grave stayed behind.

A few days later, the company was alerted that Sioux war parties were along the trail ahead…

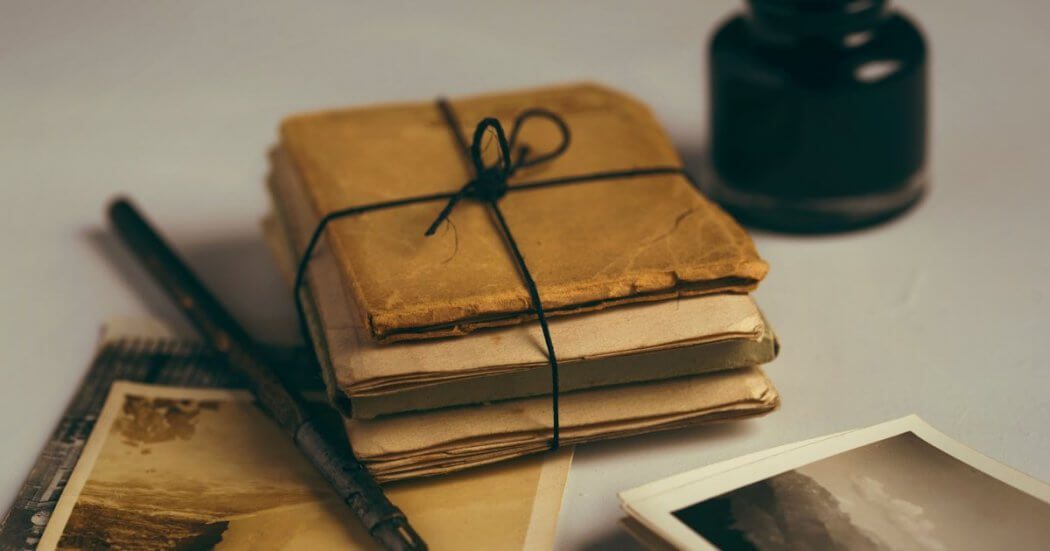

Diaries and Letters of Fellow Travelers

In an earlier chapter I mentioned that to find our stories we do not have to rely simply on what forefathers and mothers may have told or written. I found that this was especially true about the Howards when I discovered a trove of documents their fellow travelers left us. The 19th century LDS migration West – the “Mormon Pioneers” – was a vast movement of 70,000 people, a monumental saga in settling the western United States. Over the past few decades, Brigham Young University and the Historians Office of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints have collected and placed online a huge compilation of diaries, letters, newspaper articles, and other primary materials. These are a treasure for any descendant of these people.

The site is available for anyone’s use (see the footnotes or bibliography for links). The material is organized by travel parties. I followed the index to find to which parties the Howards belonged. Then, accessing the parties, I discovered day-to-day stories of Howards’ travel from London to Salt Lake City from multiple original documents. Through the eyes of those around them, it was possible to sail with the Howards and walk alongside their ox-drawn covered wagon. I heard the voices of the men and women, and girls and boys, who traveled with the Howards during that long summer of 1864…

Google Maps and Wikipedia: Take-along Tools

…once, when Seija and I were driving between Kansas City and Omaha, it occurred to me that we were close to the spot where the Howards launched their journey across the plains. We were on the interstate highway that followed the east bank of the Missouri. Somewhere along the way we would pass by the site their wagon train provisioned and departed from the river’s other side. Seija and I decided to take a detour to see what we could find.

I studied the two good sources of information that most people these days carry on their smartphones – Wikipedia and Google Maps – and soon had the coordinates for Wyoming, Nebraska. Whenever doing family history travel, carefully pre-planning is always important. However, flexibility to deviate and explore unexpected avenues should always be part of the trip. A good maps app and Wikipedia can greatly facilitate quick on-the-spot research that gives you the possibility to do this.

When we came to the I-29 exit that read “Nebraska City,” we pulled off west, took a bridge across the Missouri, and let my phone’s Google Maps guide us through a Nebraska City that no longer exuded the zeal the frontier river town must have had in the 1860’s. Within a few minutes we turned from a modern divided highway onto a narrow country lane, and soon we were on gravel roads.

Around a turn, two wild turkeys, a tom and his hen, strutted down the middle of the roadway. We stopped to watch them, wondering whether some of their ancestors might have made some very tired pioneer travelers a happy meal that summer of 1864. The turkeys dodged into the high roadside stubble, perhaps with the same thought. The rolling grassy prairie of the Howards’ times was now lush undulating north-south folds covered with the fields that made America’s Mid-West the world’s greatest breadbasket.

When we arrived at the place Google Maps marked “Wyoming,” we found a narrow dirt lane that wound down to a farmhouse, barn, and other outbuildings. On the corner of the lane and the gravel road was a dilapidated rusty sign, barely still readable, that announced, “Wyoming Acres, Main Street.” The farm below sat on a railroad line that sometime between then and now had had a stop and a post office called Wyoming. The lost spot where the Howards buried little Tamar after only two days on the trail could not have been too far from where my wife and I saw the rusty “Wyoming Acres” sign.

On the other side of the rails, the fields gently sloped downward about a mile or two to a beautifully wooded bend on the Missouri, the spot where the old town of Wyoming once stood. The river boats stopped at that peaceful mooring, and their passengers pulled off their chests and trunks full of things so precious that the families had lugged them over an unbearably long journey. There, men, women, and children began preparing for the even harder leg still ahead.

I contemplated the disparity between the place heralded as “Wyoming Acres,” and Birmingham’s “Church Lane,” where thoughts of this trip had been born. What a stark contrast there was: on one hand, the feverishly growing industrial city they left; on the other, the vast lonesome prairie that now swept before them, nearly empty for almost a thousand miles except for wild animals, hostile Sioux war parties, and fellow pilgrims. My emotions stirred deep inside, but I am sure whatever I felt was nothing compared to what the Howard family experienced the day the J. F. Lacy moored in Wyoming, Nebraska.

1 John T. Gerber, “Journal,” in Journal History of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, 26 Oct., 1846, 3-9, in The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, Pioneer Data Base, “William Hyde Company (1864),” https://history.churchofjesuschrist.org/overlandtravel/companies/166/william-hyde-company-1864. “Ann Shelton,” in “Find a Grave Memorial.” John K. Hulmston, “Mormon Immigration in the 1860s: The Story of the Church Trains,” Utah Historical Quarterly, 58:1 (Winter 1990), 44. “Amelia Slade Bennion,” in Carol Cornwall Madsen, Journey to Zion, (Salt Lake: Deseret Book, 1992), 568-569. “Joseph and Ann Shelton Howard,” John W. and Deanne Driscoll, eds. The Joseph Howard Family, (Blackfoot, ID: self-published, June 1998), 5. Randolph B. Marcy, The Prairie Traveler, A Handbook for Overland Expeditions, (New York: Skyhorse, 2014) reprint of 1859 original, 29.

2 Madsen, 314, Pioneer Database.

3 Fletcher, Pioneer Database. John T. Gerber, Pioneer Database, 26 Oct. 1864, 3-9.