Reaching Genealogical Conclusions: Hypothesis, Theory & Proof By Elizabeth Shown Mills

The following essay concerning the nature of genealogical proof was excerpted by Elizabeth Shown Mills from her book, Evidence Explained: Citing History Sources from Artifacts to Cyberspace. 3rd ed. Rev. (2017), p. 17. In it, Mrs. Mills explains the difference between genealogical proof, theory, and hypothesis and offers a cautionary point lesson that any researcher would do well to re-read from time to time.

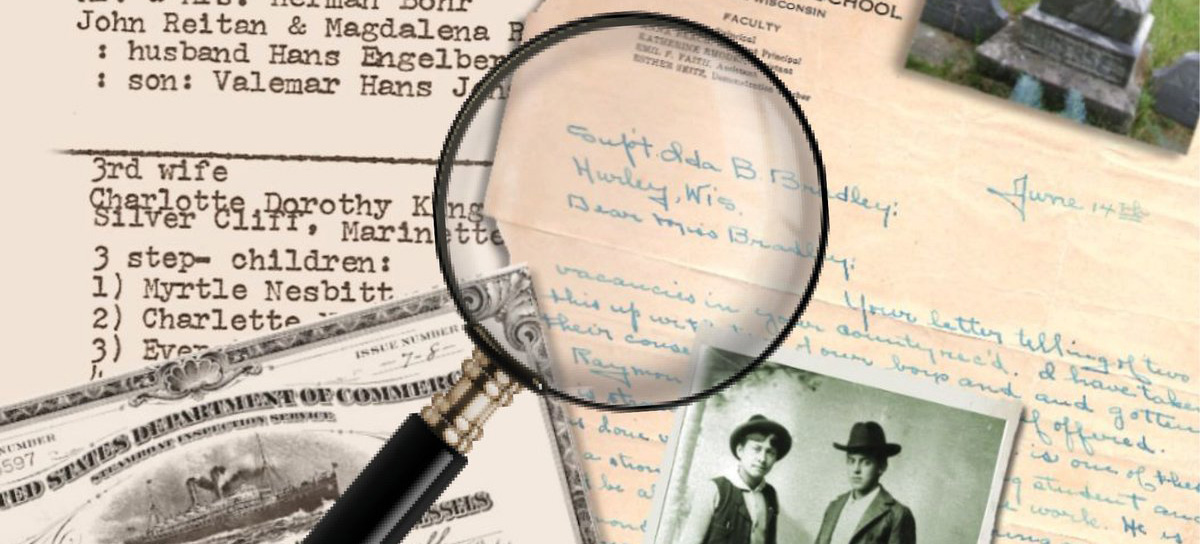

“Each and every assertion we make as history researchers must be supported by proof. However, proof is not synonymous with a source. The most reliable proof is a composite of information drawn from multiple sources—all being quality materials, independently created, and accurately representing the original circumstances.

“For history researchers, there is no such thing as proof that can never be rebutted. We were not there when history happened, and the eyewitness accounts of those who were—if and when those accounts exist—may not be reliable. Every conclusion we reach about circumstances, events, identities, or kinships is simply a decision we base upon the weight of the evidence we have assembled. Our challenge is to accumulate the best information possible and to train ourselves to skillfully analyze and interpret what it has to say.

“In this process, we typically reach conclusions of three types, each of which carries a different weight:

- Hypothesis—a proposition based upon an analysis of evidence at hand; used to define a focus for additional research. In testing any hypothesis, we must labor to disprove it as diligently as we labor to prove it. Our role is not just that of judge and jury, but also that of devil’s advocate.

- Theory—a tentative conclusion reached after a hypothesis has been extensively researched but the evidence still seems short of proof. A theory should never be presented as a fact. Any theory we propose should carry qualifiers. Perhaps, possibly, likely, and similar terms can express our degree of confidence in a theory, but we are still obliged to explain our reasoning.

- Proof—a conclusion based upon the sum of the evidence that supports a valid assertion or deduction (i.e., a conclusion drawn from assembling information from many sources). Proof must be backed by thorough research and documentation, by reliable information that is correctly interpreted and carefully correlated, and by a well-reasoned and written analysis of the problem and the evidence. “A conclusion cannot always be reached. When the accumulated materials are well appraised, the evidence may or may not support a decision. If it does not, then the question remains open—the fact of the situation remains unknown—until sufficient evidence is developed. If extenuating circumstances pressure for a decision (as with impending court testimony in a dispute over, say, historical property or heirship), then the researcher must present all relevant evidence, interpret it accurately, and appropriately qualify whatever hypothesis seems warranted. This is commonly done through the use of terms that denote levels of confidence. (See Evidence Explained 1.6.)”