Deciphering Old English Handwriting

Just about anyone who takes genealogy seriously is destined to face the challenge of reading original (or microfilm copies of) records written in an unfamiliar cursive style. If your research takes you back to at least the 19th century, you’ll encounter census records, wills, deeds, and multifarious other records that you’ll strain to decipher. Records from the colonial period will elicit a double-take if you’ve never seen them before. You’ll run into “ff” where you might expect an f,” and an “f” will actually stand for “s.” The ancient abbreviation “Maps” should be read as “Mass” for Massachusetts. The letters “U” and “V,” as well as “u” and “v,” were used interchangeably. On the whole, the following lowercase letters are most difficult to read, especially in 17th-century documents: “c,” “e,” “h,” “r,” “s,” and “t.”

Once you’ve figured out what the letters are, you’ll need to bone up on old abbreviations for terms in common usage today. For instance, “o.s.p.” is short for “died without issue.” “Yt” stands for “that.” “Als” signifies an “alias.” “D.v.m.” means “died while mother was living,” while “d.s.p.” also means “died without issue.” Did you know that “B.L.W.” means bounty land warrant, or that “do” was short for “ditto, or the same as above,” a notation you’ll encounter repeatedly in census records?

The challenges don’t end there. One has to learn to decipher numerals as well as letters. Even after you get familiar with a certain era’s lettering, you may find that what was conventional in 1700 is unrecognizable 50 years earlier. Then, of course, there is the problem of individual styles of writing.

For the novice, decoding early handwriting can be an intimidating task. If you are a beginner, you may wish to get your hands on Kip Sperry’s excellent handbook, Reading Early American Handwriting, the best tool we know of for teaching you how to read and understand the handwriting found in documents commonly used in genealogical research. This guide explains techniques for reading early American documents, provides samples of alphabets and letter forms, and defines commonly used terms and abbreviations. Perhaps best of all, the volume presents numerous examples of early American records for the reader to work with. Arranged by degree of difficulty, from the relatively easy-to-read documents of the 19th century to those of the 17th, the documents showcase examples of handwriting styles, letter forms, abbreviations, and terminology typically found in early American records. Each document–there are nearly 100 of them at various stages of complexity–appears with the author’s transcription on a facing page, enabling the reader to check his/her own transcription. This strategy allows the researcher to attain proficiency in reading the documents at a natural rate of progression.

Listen to what the experts have to say about Reading Early American Handwriting: “The further back in time our research takes us, the more ‘plain English’ looks like a foreign language. That’s why Sperry’s ‘plain English’ guide to not-so-plain English writing is an absolute basic book for every genealogical shelf,” says Elizabeth Shown Mills, CG, FASG. According to the “National Genealogical Society Quarterly,” “‘Reading Early American Handwriting’ is a timeless reference whose value will increase as more early-American documents become available to researchers of many disciplines.”

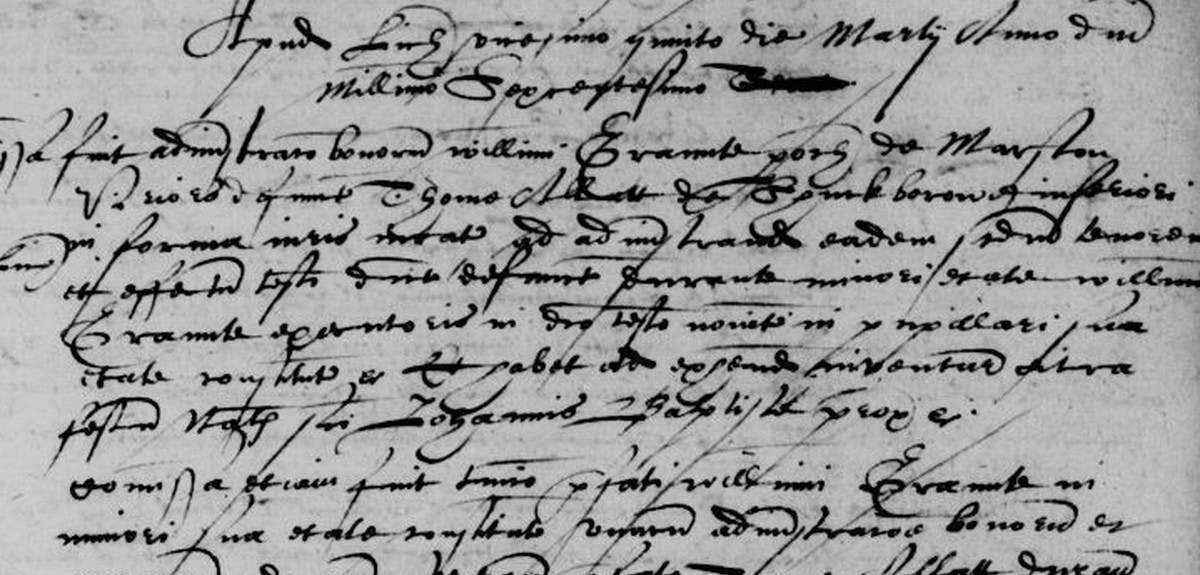

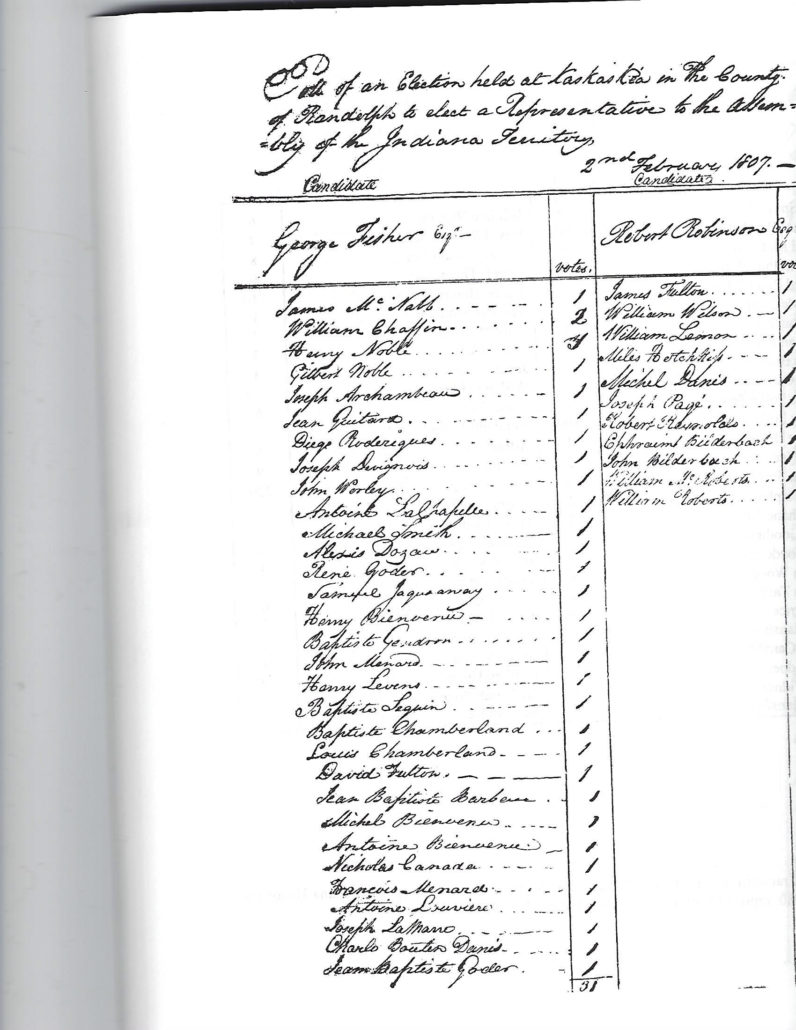

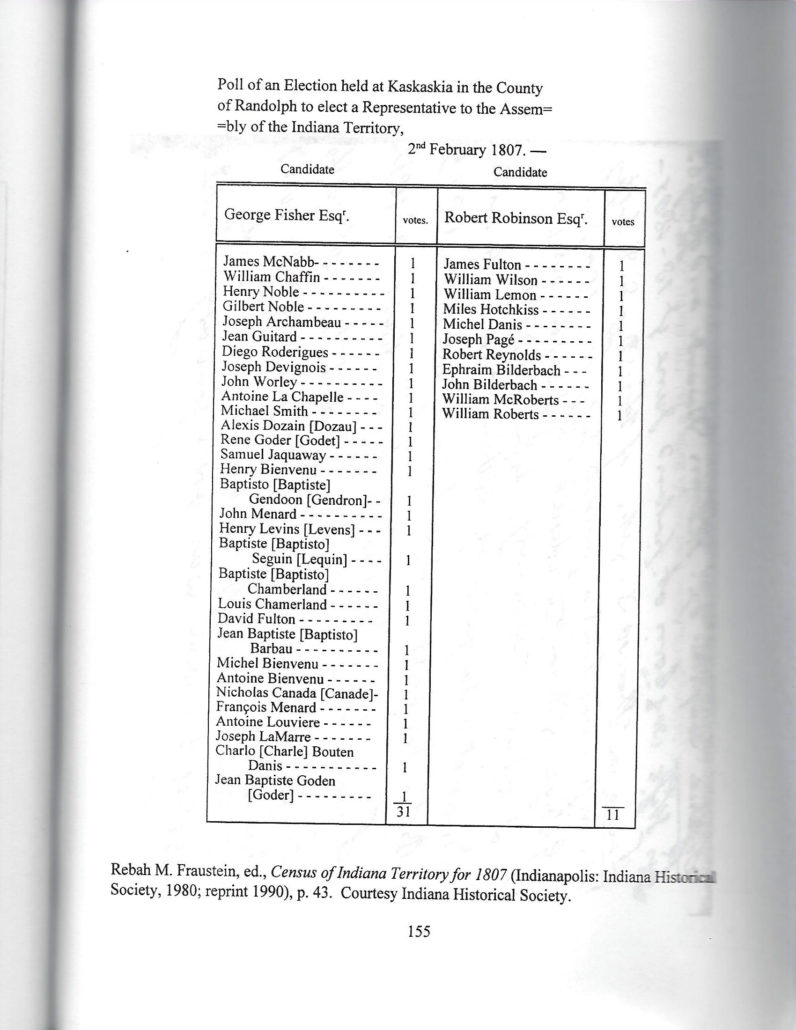

If you’re planning to consult original records of the 19th, 18th, or 17th century, or earlier, we encourage you to let Reading Early American Handwriting be your guide. Here is a link to more information about the book, and following that are two sample pages from the work showing how Mr. Sperry illustrates the translation process.

Recent Blog Posts