“The Importance of Gravestone Inscriptions in Irish Research,” by Brian Mitchell

(The following essay is excerpted from pp. 39-40 from Mr. Mitchell’s book, New Pocket Guide to Irish Genealogy.)

With civil registration of births and deaths commencing in 1864, and with the patchy survival of church records before this time, gravestone inscriptions take on a special significance. Many Church of Ireland burial registers were destroyed by fire in the Public Record Office, Dublin in 1922, while the registers of the Catholic and Presbyterian churches are especially poor regarding burial entries.

In many cases a gravestone inscription will be the only record of an ancestor’s death. Yet gravestones offer much more than just the date of death; they frequently mention the townland address of the deceased together with the names, ages and dates of death of other family members. Many graves are family plots and, as a consequence, list family members and their relationship to each other.

Church of lreland graveyards should be examined irrespective of an ancestor’s religion. It was October 1829 before a Catholic cemetery opened in Dublin at Goldenbridge. Prior to the 1820s, owing to the operation of the Penal Laws, both Catholics and Protestants shared the same graveyards. Prior to the Burial Act of 1868, which permitted dissenting (i.e. Presbyterian) ministers to conduct burial services, the Church of Ireland clergy held jurisdiction over funeral services for all Protestants. Right up to the mid-19th century, it is not uncommon to find Presbyterian ministers and Methodist preachers buried in a Church of Ireland graveyard.

It is, unfortunately, true that the unkept state of many graveyards (especially those now isolated from a functioning church) and the weathering of headstones precludes the reading of many inscriptions. It is not unusual to be able to read clearly an inscription of the 18th century incised on hard Welsh slate, while those of the late 19th century, inscribed on soft limestone and sandstone headstones, have been eroded away. It must also be said that many burials in graveyards are not marked by headstones.

The gravestone located in First Garvagh Presbyterian Church, County Derry, which played its part in unravelling the McCook family story, illustrates very nicely just how much information can be gleaned from an inscription:

In memory of Alexander

McCook who died in the

year 1872, aged 58 years

and of his wife Jane who

died in the year

1881, aged 66 years

his son Archibald McCook died 19 September

1915, aged 77 years

his wife Catherine died 5 December 1917 aged 72 years

Their children

Catherine died 18 February 1885 aged 7 years

Graham died in infancy and their daughter

Margaret McCullough died 4 December 1941 aged 60 years

Hugh died 24 April 1960 aged 73 years

Mary died 11 August 1963 aged 90 years

Elizabeth, wife of Hugh died 1 November

1977 aged 79 years

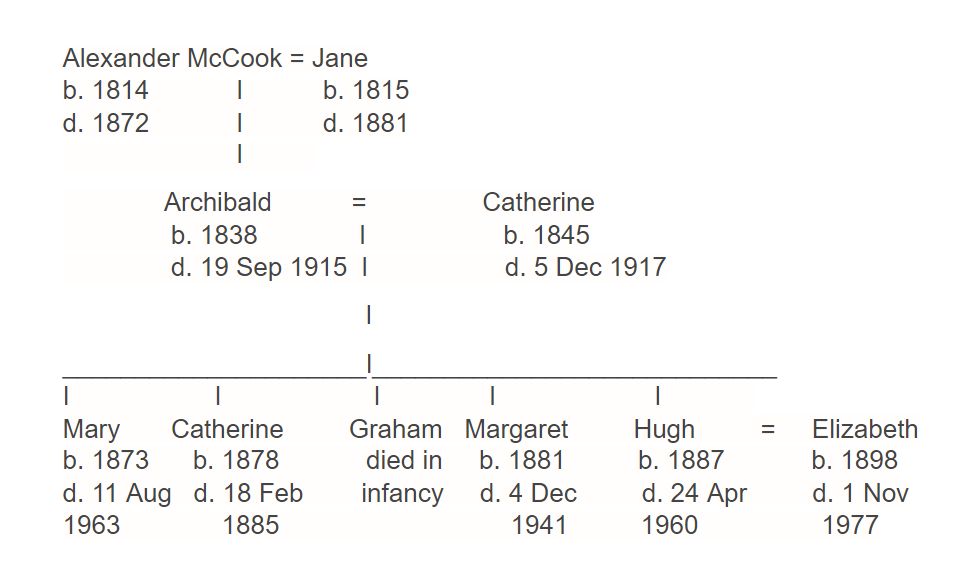

From this inscription, the following family tree stretching over three generations can be drawn:

The identification of a gravestone will open many avenues for further research. Taking our example, the civil registers could be searched for the birth certificates of Archibald’s children; the baptisms of Archibald and his father, Alexander, could be looked for in the baptism registers of First Garvagh Presbyterian Church, which commence in 1795; civil death registers can be searched and in the case of Alexander McCook and his wife, they would provide their exact dates of death; the 1901 and 1911 census returns should record Archibald and his family, while a will of Archibald McCook, if he made one, should be an easy matter to identify, as we know his date of death.

Clearly, on identifying an ancestor’s residence, the local graveyards should be visited. The Ordnance Survey maps, at a scale of six inches to one mile, with the earliest edition dating back to the 1830s, should be consulted at a local library or online, to identify all possible graveyards.

Researchers should be aware that many old graveyards are not separated from a functioning church. With the establishment of new churches throughout the 19th century, many graveyards attached to the old church fell into disuse as new graveyards were opened beside a new church. The new church and graveyard were often located some distance away from the old church and graveyard.

You can view modem, satellite and historic maps, including 6 inch maps (1837-1842) and 25 inch maps (1888-1913), of townlands of Republic of Ireland with Ordnance Survey of lreland Map Viewer at https://webapps.geohive.ie/mapviewer/index.html.

You can view historic maps, including first edition (1832-1846), second edition (1846-1862), third edition (1900-1907) and fourth edition (1905-1957) Ordnance Survey maps, modem maps and aerial photographs of townlands of Northern Ireland with Public Record Office of Northern Ireland’s Historical Maps viewer HERE. A Guide to Irish Churches and Graveyards (Brian Mitchell, Genealogical Publishing Company, Baltimore, 1990) locates every church and burial ground in mid-19th-century Ireland in relation to a townland or street address. Each townland is located in its appropriate civil parish, and each parish is listed in alphabetical order in its county.