Land Transfer Model Four: Federal Lands

In the April 7 and 14, and May 12 issues of “Genealogy Pointers,” we described three systems by which land was transferred by Colonial and Early National authorities to individuals in America: The New England Model, the Colonial Government System of Land Transfer, and the Large Grant/Proprietor System. As Patricia Law Hatcher explains in her definitive study of U.S. land records, first transfer varied both geographically and chronologically throughout the British colonies and the future United States. This fourth and final installment of the land transfer process describes the transfer of parcels in both expanding urban areas and in territories made available for settlement as population expanded westward. It is reprinted verbatim below, from pp. 75-78 of Pat Hatcher’s Locating Your Roots. Discovering Your Ancestors Using Land Records.

After the Revolutionary War, the states—sometimes reluctantly–relinquished their ungranted western lands to the federal government (see chapter six, Public Land). The majority of American land acquired by individuals was initially public land belonging to the federal government. The ultimate disposition of those public lands was:

- one-third sold to settlers

- one-third given or sold to speculators, railroads, and so on (much of which was resold to settlers)

- one-third remained in public domain.

The federal-land model most closely resembles that of New England. The land was surveyed before sale, marked out in townships, ranges, and sections. Portions were reserved for public purposes. As the survey for an area was completed, a land office was opened to sell land in the area, which often covered a significant portion of a state. Thus, our westward expansion occurred in a continual, but controlled, series of small waves as each new office opened, much like the settlement pattern in New England.

BIG CITIES AND SMALLER TOWNS

In the confined areas of cities and towns, the indiscriminate survey system obviously isn’t practical. Most municipalities of any size are developed under a system of subdivision. This is similar to the process followed in New England, in which streets and public areas were designated in the survey and lots were sold by number (albeit with an underlying metes-and-bounds description). However, the buyer chose the lot he wanted.

The developer may have been an individual seeking profit, or a group of commissioners or trustees may have been designated to administer the sales, as for the town of Glasgow, Kentucky.

“Deed 7 Jun 1800 from Haiden Trigg, Abel Hannon, William Welsh, John Cole, John Moss, John McFerran, John Matthews (trustees for town of Glasgow) to Rhody Fuell for $26: lot #25 in Glasgow, Barren County, Kentucky.”

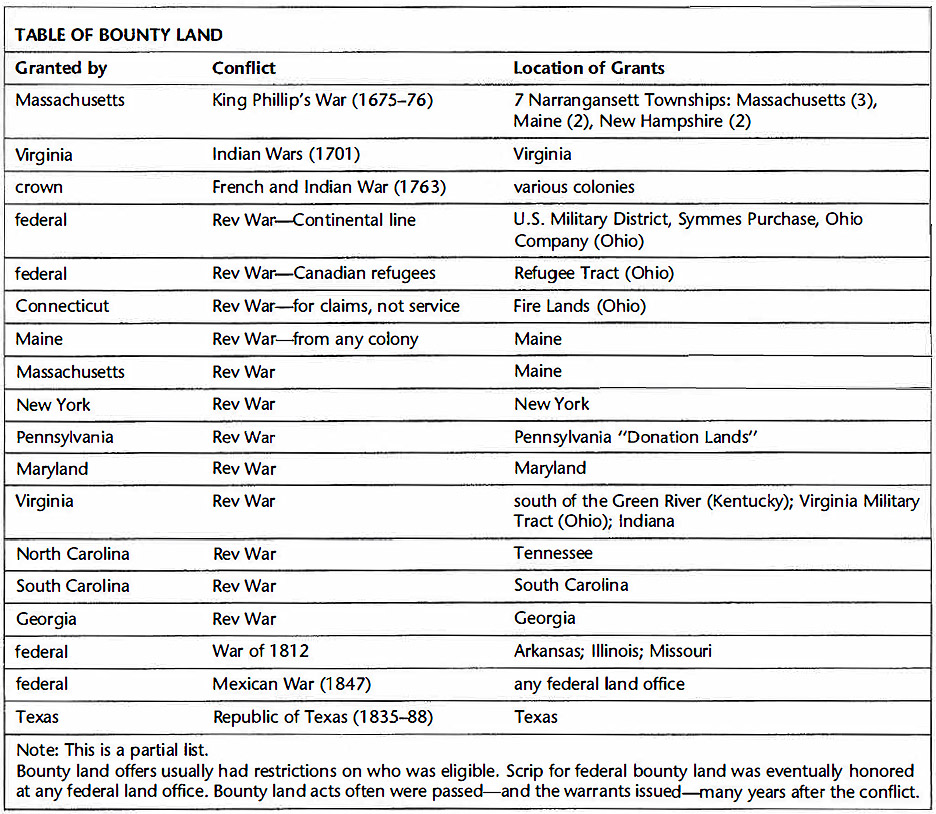

BOUNTY LAND

Colonies used land as rewards for public service (political patronage is not a new institution) and as incentive or payment, particularly for military service. In primarily agricultural America, military campaigns were significant disruptions in the planting and harvesting cycle. Some of the greatest damage of King Philip’s War in New England in 1675 and 1676, for example, resulted not from the direct conflict, but from a missed growing season on the part of both the colonists and the Indians. This war also represented the first campaign in which land was used as bounty to reward for military service.

The Revolutionary War saw a major increase in the use of bounty land, with Virginia and North Carolina making significant use of the incentive at the state level, as did the federal government. Bounty land continued to be offered through federal-period conflicts, most notably the War of 1812.

However, because land was relatively cheap and available throughout the colonies (later states), military bounty land wasn’t necessarily a strong inducement. When bounty was offered and accepted, the man who gave the military service often didn’t settle the land. Instead, he assigned the scrip or warrant he had received for whatever cold, hard cash he could get from an agent who was buying and consolidating bounty-land rights.

Colonial and State Bounty Land

During the colonial period, bounty land was offered as inducement for service or as recompense for service, injury, or death during military conflicts, mostly with the Indians and the French.

During the Revolution, colonies continued the practice, especially as the conflict dragged on and they had little cash. The introduction to Bockstruck’s Revolutionary War Bounty Land Grants Awarded by State Governments describes the practice of each colony and is recommended reading (don’t just look for your ancestor’s name).

Records related to any bounty land offered in the colonial period would be under the custody of the appropriate state, with the exception of the Virginia Military District warrants that were converted into land, which are in the possession of the National Archives. You will have to research the records to determine the location and best method of access.

Federal Bounty Land

The federal government began offering bounty land in 1776 as inducement for a man to enlist—and stay enlisted—during the Revolutionary War. It continued to issue bounty land for service through 1855. See “Bounty Land Warrant Records” in Guide to Genealogical Research in the National Archives for more information.

Remember that bounty land was not necessarily taken up by the man eligible for the bounty. Your ancestor might have been involved at either end of the process. He might have given service, received a bounty-land right, certificate, or warrant, and then sold (assigned) it to someone else. If that person was an agent, he in turn sold (assigned) it to the individual who wanted to settle the land. If this person was your ancestor, then he didn’t necessarily have military service, even though he took up bounty land.

Warrants for the Revolutionary War and War of 1812 could be used only in specified areas. When it became clear that the amount of land was insufficient, new claimants received bounty-land scrip and existing warrants could be exchanged for scrip. Warrants and early scrip were for land in Arkansas, Illinois, Indiana, Michigan (the land was considered so undesirable that it was soon withdrawn), Missouri, and Ohio. In 1842 it became possible to redeem the scrip at any federal land office, prompting increased settlement in the other states.

When requesting a copy of a bounty-land warrant, you must provide the act of Congress, certificate number, and, for acts between 1847 and 1855, the acreage. There are name indexes for the Revolutionary War and the War of 1812. Use NATF 85 to order bounty-land warrant applications. Use NATF 80 to request a search for warrants from acts between 1847 and 1855. See www.archives.gov for more information. You can request form NATF 85 easily from the website. The form comes with instructions. View Locating Your Roots. Discovering Your Ancestors Using Land Records

SEE TABLE OF BOUNTY LAND BELOW

Recent Blog Posts