Census Records and County Boundary Changes, by William Dollarhide

All censuses taken since 1790 are tabulated and organized by the counties within each state or territory. By federal precedence, the county is the basic unit of jurisdiction for census demographics. Alaska is the only state without counties; therefore, judicial districts are used as jurisdictions for the censuses taken there. In Louisiana, the term “parish” is used in the same way as “county” in other states. Even in the New England states–where a town may have more importance than a county as a genealogical resource–censuses are organized by county.

Interestingly, Connecticut abolished county government in 1960. All county functions were taken over by the towns or by the state, except that the county boundaries were retained expressly for the purpose of taking a census and certain other statistical studies based on a county, rather than town boundaries.

Between 1790 and 2000, 138 counties reported in the censuses have been renamed or abolished and subsequently absorbed into other counties. Through 1920, 44 cities in Virginia were independent of any county.

Genealogists learn early the importance of the county as a jurisdiction when using the U.S. federal censuses because one needs to know the county before one can find a resident in a certain locale. Finding the right county is a big step in genealogical research, not only because of census records but also because of the many other records specific to a certain county or locality.

County Boundary Changes:

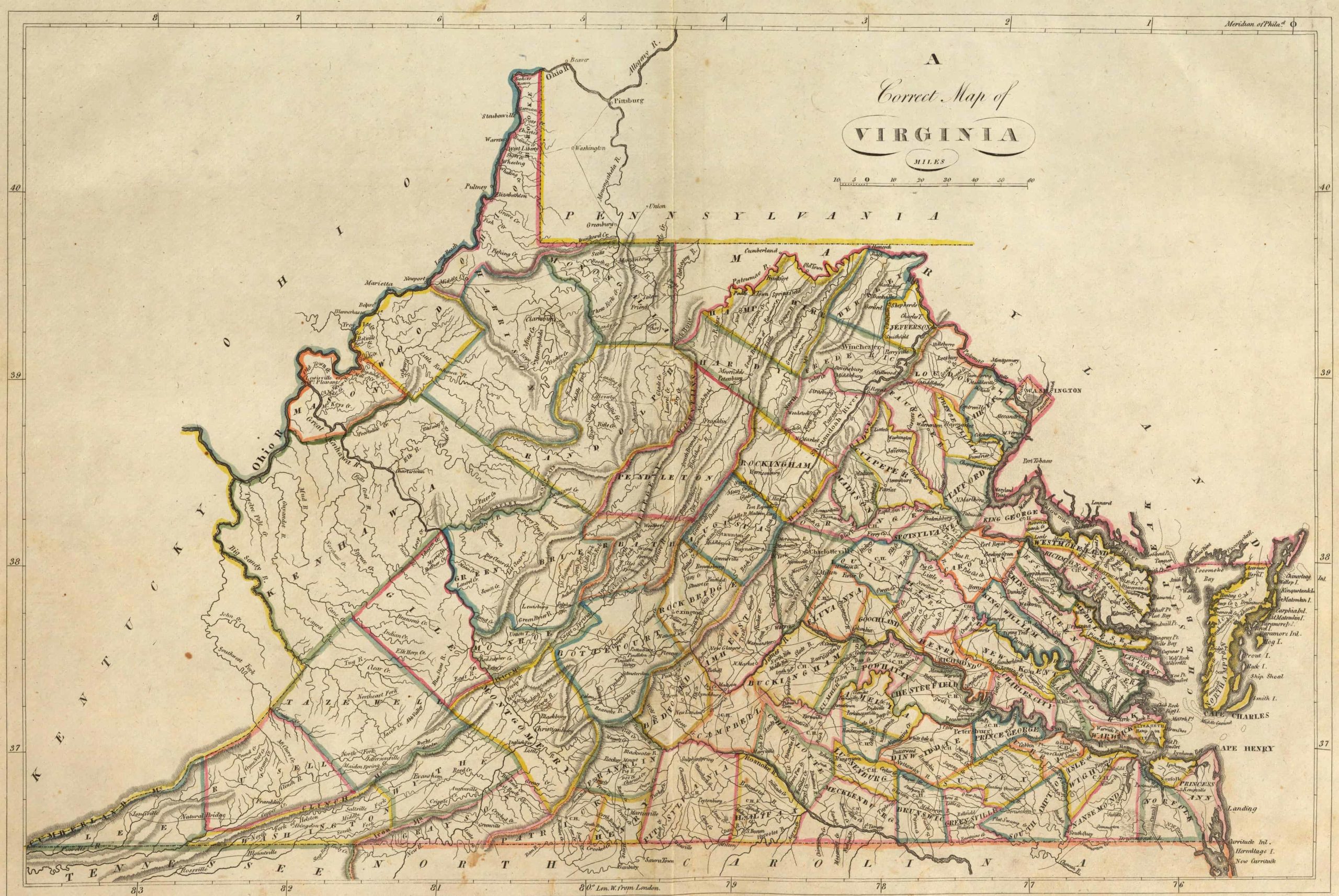

When using census records for genealogical research, researchers need to understand how county boundaries have changed over the years. Understanding the genealogy of counties is part of locating the place where an ancestor lived.

For example, if a genealogist knows that an ancestor lived in Allegheny County, Pennsylvania, in 1790, that county’s courthouse is a resource for old deeds, marriages, and other court records. By 1800, nine new counties had been created from old Allegheny County, covering the same area: Allegheny, Beaver, Butler, Crawford, Erie, Mercer, and parts of Armstrong, Venango, and Warren counties.

Another example of county boundary changes occurred in Oregon. In 1850, marriages in the little town of Linkville in Linn County were recorded in Albany, the county seat. By 1860, due to the formation of new counties, marriages performed in Linkville, now in Wasco County, were recorded in The Dalles; in 1870, marriages performed in Linkville were recorded in Jacksonville, the county seat of Jackson County (but later the county seat was moved to Medford); in 1880, marriages performed in Linkville were recorded in Lakeview, the county seat of Lake County; and in 1890 marriages performed in Linkville were recorded there because Linkville had become the county seat of Klamath County–but then the name Linkville was changed to Klamath Falls. The boundaries of Klamath County have not changed since 1890.

Of course, the town of Linkville never moved. As the settlement of Oregon took place, new counties were created, and earlier county boundaries were changed, placing the town of Linkville-Klamath Falls in five different counties from 1850 through 1890. Therefore, all county records such as deeds, probates, marriages, etc., for a family that lived in Linkville, Oregon, are spread across the state and stored today in five different county courthouses.

These examples can be repeated in virtually every state. Genealogists attempting to identify the places their ancestors lived must first face the reality of changing county boundaries over the years.

A source that can be used to visualize the county boundaries for every county in the U.S. and for each census year is the book by William Thorndale and William Dollarhide, Map Guide to the U.S. Federal Censuses, 1790-1920 (Genealogical Publishing Co., Inc., 1987). This book has 393 maps showing each applicable census year and all county boundary changes from 1790 to 1920. Each map shows both the old boundaries and the modern boundaries for each state and census year, so a comparison can be made. A fuller description of this book appears in the article below.

Guides for Census Research

As the foregoing article illustrates, Mr. Dollarhide knows a thing or two about county boundaries and census records. He is co-author with William Thorndale of Map Guide to the U.S. Federal Censuses, 1790-1920, one of the most respected books in all of American genealogy. More recently, Mr. Dollarhide has compiled a directory of censuses and census substitute lists for New York. This recent book, New York State Censuses & Substitutes identifies every census or similar population list compiled by New York or its various counties from the colonial period on.

Below are brief descriptions of both of these books, plus other tips for discovering hidden state and colonial censuses.

Map Guide to the U.S. Federal Censuses, 1790-1920

The author of “Genealogy Pointers” once studied the population of Baltimore from the vantage point of the 1850, 1860, and 1870 federal censuses. Throughout the period, Baltimore was divided into 20 wards (political subdivisions); however, as his research revealed, the ward boundaries changed with each census. Had he failed to consider these boundary changes, his conclusions concerning the ethnic and racial makeup of Baltimore’s 19th-century neighborhoods would have been incorrect.

Whether because of political gerrymandering, annexation, or some other reason, county boundaries–like ward boundaries–were subject to frequent change. For example, the boundaries of both Somerset and Worcester counties on Maryland’s Eastern Shore changed between 1860 and 1870 to make room for the new county of Wicomico. Between 1850 and 1860, the eastern part of Yalobusha County, Mississippi, became part of Calhoun County. Ten years later, the southern part of Yalobusha could be found in Grenada County.

The fact is that throughout U.S. history, county boundaries changed from one decennial census to the next, especially before 1900. The best way to know if you’re looking in the right county as you crank or scroll through the census is to consult the MAP GUIDE by William Thorndale and William Dollarhide. State by state, this highly acclaimed reference work maps out county boundaries for every census from 1790 through 1920 and superimposes modern county boundaries overtop of them. Don’t be lost in the census without it!

More Census Reference Works

New York State Censuses & Substitutes

Census records and name lists for New York are found mostly at the county level, which is why this new work shows precisely which census records or census substitutes exist for each of New York’s 62 counties and where they can be found. In addition to the numerous statewide official censuses taken by New York, this work contains references to census substitutes and name lists for time periods in which the state did not take an official census. It also shows the location of copies of federal census records and provides county boundary maps and numerous state census facsimiles and extraction forms.

State Census Records

When genealogists think of census records, what usually comes to mind are the federal censuses that have been conducted by the U.S. government every 10 years since the formation of the country. It’s a fact, however, that state governments have also carried out censuses randomly throughout their history to satisfy a variety of purposes. Michigan, for example, took a special Civil War veterans census in 1888. There are also surviving territorial censuses that were taken to demonstrate readiness for statehood.

These state censuses are invaluable to genealogists because they fill in gaps left by missing federal censuses. For example, 12 states conducted censuses between 1885 and 1895, any one of which can substitute for that state’s missing 1890 federal census. State censuses tend to be opened to the public faster than federal ones; some state censuses taken as recently as 1945 are already available. Many state censuses contain information not found in federal censuses because the census takers asked different questions. For all of these reasons, state censuses can give you a more complete picture of your ancestors and solve genealogical problems. To find out what state censuses exist, what kinds of information they contain, and where they can be found, read State Census Records, by Ann Lainhart, the definitive guide to this major, though vastly under-used, genealogical resource.

American Population Before the Federal Census of 1790

Few books published more than 70 years ago are just as useful to the genealogist today as they were in 1932. Evarts B. Greene and Virginia D. Harrington’s American Population Before the Federal Census of 1790 is one such book. The recipients of a social science research grant, Columbia University scholars Greene and Harrington set about to compile a list of every 17th- and 18th-century list (or statistical reference thereto) concerning the American population before the first U.S. census of 1790. Consulting both primary and secondary sources, the end result of their labors was a comprehensive survey, arranged by colony, state, or territory–and chronologically thereunder–of population lists for all units of American government in existence as of 1790.

The lists themselves range from poll lists, tax lists, taxables, militia lists, and censuses; the book’s geographical coverage extends to Connecticut, Delaware, Georgia, Kentucky, Maryland, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, New Jersey, New York, North Carolina, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, South Carolina, Tennessee, Vermont, Virginia, the Illinois Territory, and the Northern and Southern Departments of the Western Indians.

In all, American Population Before the Federal Census of 1790 refers to about 4,000 separate population lists or estimates. The authors provide the sources for all entries, which are keyed to the extensive bibliography at the beginning of the book. While researchers will find no lists of persons in this volume, they will discover what exists and where to find it in this crucial record category of early American records. Little wonder that amateurs and professional researchers today prize this book as much as it was in 1932!

Recent Blog Posts