Will Your Genealogy Pass the Test of Time? by Richard Hite

[av_image src=’https://genealogical.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/09/2017-11-05-05-34-06.1f57953c24fd8041d68074e472523f5cb3720209-223×300.jpg’ attachment=’5382′ attachment_size=’medium’ align=’right’ styling=” hover=’av-hover-grow’ link=’manually,https://library.genealogical.com/printpurchase/ozld5′ target=’_blank’ caption=’yes’ font_size=” appearance=’on-hover’ overlay_opacity=’0.4′ overlay_color=’#000000′ overlay_text_color=’#ffffff’ animation=’no-animation’ admin_preview_bg=” av_uid=’av-5u4eyp’]

View Book Details

[/av_image]

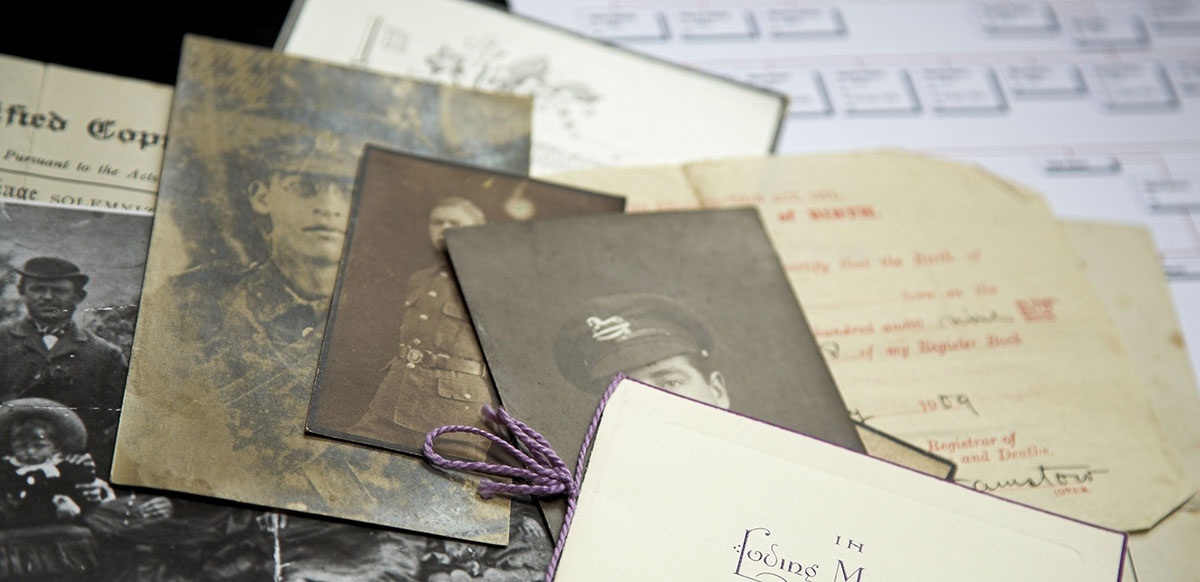

Sustainable Genealogy: Separating Fact from Fiction in Family Legends, by Richard Hite, is a wonderful collection of cautionary tales for the practicing genealogist. In the following selection from Sustainable Genealogy, Mr. Hite illustrates where and why genealogists go astray when they uncritically accept information found in old county histories, oral history, and even in official death records!

“It is not always easy to distinguish fact from fiction in oral history. There are, however, certain guidelines one can follow in terms of guessing how accurate a family story an older relative told is likely to be. We must ask ourselves several questions:

- Did the informant know the people involved?

- If so, how old was the informant when the people involved died?

- Whether or not the informant knew them, did he or she grow up in the same vicinity as the people in the story?

In the case of my grandmother, she did not know her grandmother, Mary (Hambleton) Bush, who died in 1881, nineteen years before Grandma was born. She did spend her early childhood in the same area that her grandparents had lived in as adults and may have known some of her grandmother’s siblings. She was right about the Quaker connection, but she was wrong about the first name of her great-grandfather Moses Hambleton and also about the spelling of her grandmother’s maiden name (she had probably only heard it and never saw it written, so it is understandable that she remembered it as Hamilton). It is noteworthy that she did correctly remember the first name of Moses Hambleton’s wife Matilda. The reason for that is obvious. Her own mother had been named Matilda, for this grandmother, and evidently often mentioned that she had been named for both grandmothers, a fact that her daughter Jessie knew very well. Jessie had not correctly remembered Matilda Hambleton’s maiden name, but that name had not been incorporated into Matilda Bush’s name, so it was less significant.

Biographical accounts in county histories should be subjected to similar criteria. A discerning genealogist will first check the date of publication and then address the following questions:

- Which of the people mentioned in the account were living at the time of publication?

- Which ones mentioned as ancestors of the subject lived into his/her lifetime?

- Which ones are described as having lived in or near the area the subject lived in?

- How glamorous is the account of the subject’s ancestors? (If it seems overly glamorized, it has to be examined particularly closely. Particularly questionable are heroic military feats or the overcoming of extreme hardships or personal tragedies. Those things did happen, but not as often as reported by county histories).

For accounts on the Internet, if a source has not been cited, a discerning genealogist should contact the person who posted it. If the poster names a printed or primary source, that source should be checked. If the poster only says it was something an older family member told (or fails to identify any source) then it should be treated the same as an account from one’s own older family members.

It Even Creeps into “Primary” Sources

Published county histories and accounts on the Internet are not the only sources of “written oral history.” Some aspects of sources generally regarded as “primary” should also be viewed in that way. Perhaps the best such example is death certificates. Only certain items on them are truly “primary.” The date and place of death of the decedent may be considered primary source information, because the death is the event that the certificate records. Other information on the certificates however – including that which is most useful to genealogists – cannot be regarded as “primary”.

The death certificates of most states ask for the date and place of birth of the decedent and the names and birthplaces of the decedent’s parents (including the mother’s maiden name). When provided, they are a genealogical gold mine – but not one that can be automatically accepted without checking other sources. The person providing the information is unlikely to have been witness to the decedent’s birth (unless the informant is a parent of the deceased, which is unusual). Most often, informants are spouses or children of the deceased and their memories of the names and birthplaces of the decedent’s parents must be verified with other sources before being considered confirmed. The same questions must be asked about informants for death certificates that must be addressed in regard to those who tell life stories of their parents or grandparents to younger family members. Obituaries must be subjected to similar criteria if they give information on parents and more distant ancestors of the decedent.

Every Family Has Stories

Every family has unique stories, some accurate, some only partly accurate, and some entirely fictitious. Although each story is different, there are certain patterns that consistently emerge in family after family. Certain types of errors in oral traditions are found again and again. Genealogists should always be on the lookout for them and research primary sources to prove or disprove them because all are important to genealogists. In many cases, the same errors happen in different family stories for similar reasons. The following list includes some of the types of information provided in the various forms of oral history that most often turn out to be in error:

- Ethnic Origins of Family Names

- Maiden Names of Female Ancestors

- Relationships to Someone Famous

- Relationships to Royalty, Nobility, or Wealth

- Birthplaces of Ancestors

- Military Service of Ancestors

- Two or More Brothers as Immigrants

- Associations or Encounters With Famous People

- Native American Ancestors

For all of these traditions, and many others, the information in oral history may be accurate or at least partially accurate. It should not be accepted as factual, however, until it can be verified with primary source material.” For more information about Sustainable Genealogy: Separating Fact from Fiction in Family Legends, click the button below.

[av_button label=’View Sustainable Genealogy Details’ link=’manually,https://library.genealogical.com/printpurchase/ozld5′ link_target=’_blank’ size=’large’ position=’center’ icon_select=’yes’ icon=’ue84f’ font=’entypo-fontello’ color=’theme-color’ custom_bg=’#444444′ custom_font=’#ffffff’ admin_preview_bg=” av_uid=’av-3n16yp’]

[av_button label=’Preview Book with LOOK INSIDE’ link=’manually,https://library.genealogical.com/preview/sustainable-genealogy-2′ link_target=’_blank’ size=’medium’ position=’center’ icon_select=’yes’ icon=’ue84e’ font=’entypo-fontello’ color=’black’ custom_bg=’#444444′ custom_font=’#ffffff’ admin_preview_bg=” av_uid=’av-7moep’]

Recent Blog Posts