History for Genealogists—More than Timelines

As the subtitle–Using Chronological Time Lines to Find and Understand Your Ancestors— to the 2016 expanded and revised edition of Judy Jacobson’s best-selling book, History for Genealogists indicates, this sought after book contains scores of historical chronologies that genealogists can access in order to place their ancestors in time and place. As Judy puts it:

“Genealogy lays the foundation to understand a person or family using tangible evidence. Yet history also lays the foundation to understand why individuals and societies behave the way they do. It provides the building materials needed to understand the human condition and provide an identity, be it for an individual or a group or an institution.”

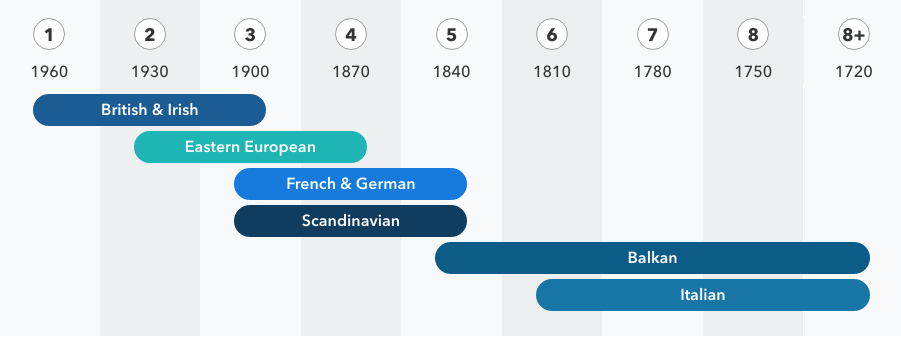

That said, we would not want readers to overlook the many valuable narrative elements contained in History for Genealogists. For example, the chapter on new arrivals to America contains a number of important tables showing 19th-century migration patterns. Similarly the new chapter on “Fashion and Leisure,” prepared by Denise Larson discusses the 19th-century relationship between the growth of amateur sports and recreational swimming and the time constraints imposed upon workers by the industrial revolution.

One of the most fascinating chapters in the new edition is entitled “Even Harder to Find Missing Persons.” Here Mrs. Jacobson addresses such thorny genealogical problems as finding slave ancestors, origins of the “Orphan Train” riders, record challenges created by boundary changes, and the matter of isolated societies. By “isolated societies” Jacobson is referring to groups such as the Mellungeons of Appalachian Kentucky, Tennessee, and North Carolina; the “Cajans” of the Spanish frontier of Alabama; the Lumbees or Croatans of North Carolina; the Nanticokes of southeastern Delaware; and others. Most of these groups possess mysterious origins and a number of them are mixed-race in make-up. According to Jacobson, as many as 200 multiracial groups of isolated societies could exist in the U.S., and for reasons that should be obvious, delving into the ancestry of any one of them could require the skills of a Sherlock Holmes.

Throughout the 18th century, thousands of Americans settled on the western frontier. Some of these settlements were encouraged and even owned by existing state/colonial governments. Others were purely speculative ventures. Most of them involved conflicts between settlers and indigenous people. As Mrs. Jacobson describes, three of these settlements [Franklin (now in Tennessee), Transylvania (absorbed into Virginia), and Westmoreland (now part of Pennsylvania)] established their own governments and actually vied for statehood in the new nation after 1776. While the original names of these settlements have fallen into disuse and any hope their leaders had had of achieving statehood had been dashed by the end of George Washington’s presidency, genealogists hoping to find ancestors during the era of these independent territories, need to know about them. Following is Judy Jacobson’s brief description of Franklin, Transylvania, and Westmoreland. View History for Genealogists