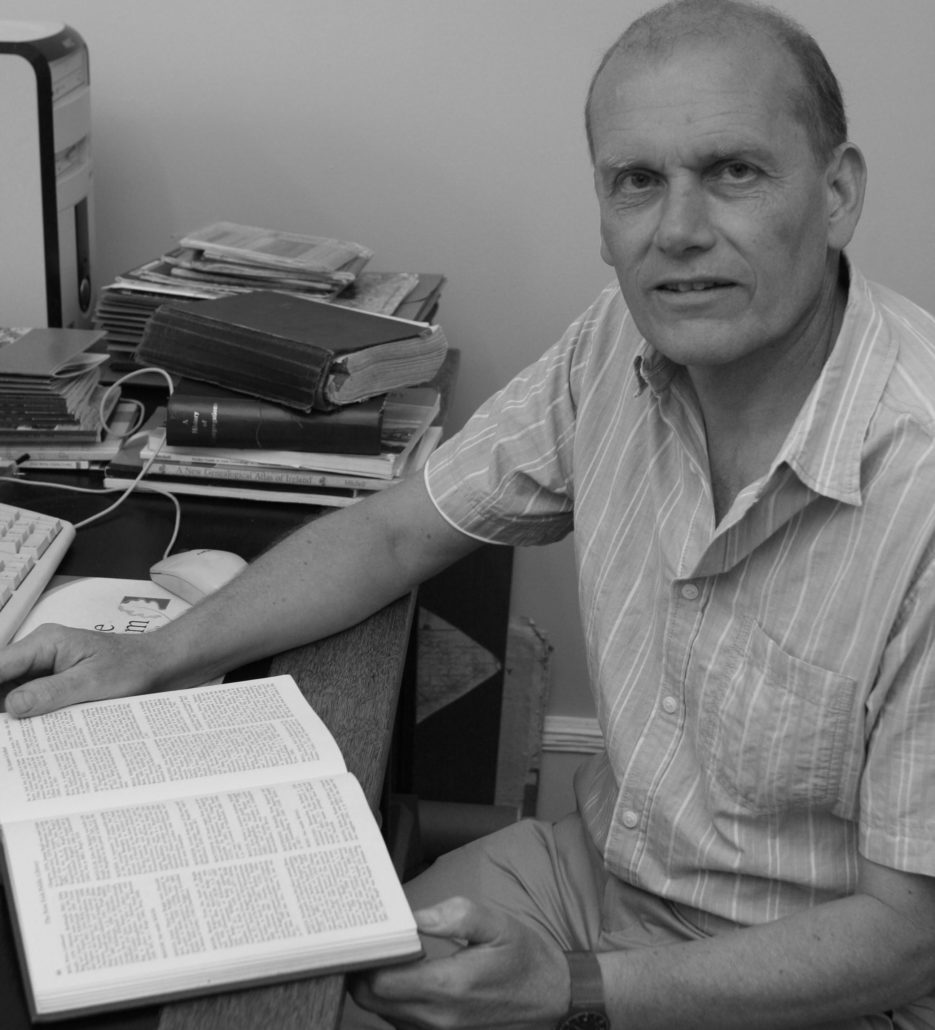

Tracing Irish Ancestry: A personal viewpoint, by Brian Mitchell

It is amazing to witness how far Ireland has come in the last decade in terms of making record sources available online! You can now achieve so much online: to name, but a few, you can search 1901 and 1911 census returns at www.census.nationalarchives.ie; historic civil birth, marriage and death registers at www.irishgenealogy.ie; transcripts of numerous church registers, of all denominations, at www.rootsireland.ie; pre-Famine and post-Famine census substitutes at, respectively, www.titheapplotmentbooks.nationalarchives.ie and www.askaboutireland.ie/griffith-valuation.

For me, genealogy is really a mix of geography and local history, and it just so happens that these two topics have always fascinated me. I tend to see genealogy as a means to make connections between people and place as opposed to tracking family lineage back in time, generation by generation.

Not only does geography and knowledge of place offer more potential for researchers to feel an emotional attachment to that part of Ireland associated with their ancestors, it also enables realistic genealogical research which, in the absence of indexes and databases, generally requires knowledge of the parish in which your ancestor lived.

There are 32 counties and 2,508 civil parishes in Ireland. Researchers can identify Ireland’s network of civil parishes at www.johngrenham.com/places/civil_index.php.

A driving force among most people tracing their family history is to identify an ancestral home; to stand on land where the family house would have stood centuries ago. In Ireland this, in effect, means identifying the townland your ancestor lived in.

There are 60,642 townlands in Ireland. You can search the Townland Index online, to pinpoint county, civil parish and poor law union locations for more than 65,000 place names in Ireland, by using the “placename” search option at www.johngrenham.com/places.

A database of administrative placenames (townlands, parishes, towns etc.) for Ireland, in both Gaelic and English, can be searched in ‘The Placenames Database of Ireland’ at www.logainm.ie, and at www.placenamesni.org you can identify the location, origin and meaning of over 30,000 placenames from all over Northern Ireland.

To get a feel for the area that your ancestor lived in you should always explore maps. Between 1829 and 1842 Ordnance Survey Ireland completed the first ever large-scale survey of an entire country. These maps were surveyed on a county basis. Hence, a record of townland names, shapes and sizes for all Ireland exist in these maps at a scale of six inches to one mile.

You can view modern, satellite, and historic maps – including 6-inch maps (1837–1842) and 25-inch maps (1888–1913) – of townlands of Ireland with Ordnance Survey of Ireland Map Viewer at http://map.geohive.ie/mapviewer.html.

For the townlands of Northern Ireland, you can view historic maps – including first edition (1832–1846), second edition (1846–1862), third edition (1900–1907), and fourth edition (1905–1957) Ordnance Survey maps – together with modern maps and aerial photographs with Public Record Office of Northern Ireland’s Historical Maps viewer at www.nidirect.gov.uk/services/search-proni-historical-maps-viewer.

Ireland, furthermore, has a very strong tradition of researching and publishing histories of local communities, and I would encourage all researchers, with ancestors associated with known townlands and parishes, to seek them out in libraries and archives. Such local history publications will provide historical context (local history, family history, emigration history) to their ancestors’ links with Ireland. Indeed, many local history publications will contain knowledge/oral traditions, which may not be found in any historical documents and/or captured in any database.

I would see local history publications in similar vein to a DNA test as a tool to aid genealogical research. In purchasing DNA tests researchers are hoping that they ‘match’ with someone who may hold more information about the family tree than they currently hold, either in the form of historical documentation or oral tradition.

I will finish with two examples that demonstrate the breadth of knowledge and insight that can be gleaned from local history publications:

1) Aghadowey: A Parish and its Linen Industry by Reverend Thomas H Mullin (Belfast, 1972)

This book is an extremely comprehensive local and family history of Aghadowey, a parish in the Bann Valley district of County Derry. At the Plantation of Ulster, in 1615, the Ironmongers’ Company of the city of London were granted a large estate in the Bann Valley, centred on Aghadowey.

In appendices in Rev. Mullin’s book are named adults deemed capable of military service in Muster Roll on Ironmongers’ Estate dated c. 1630 and the names of tenants on the estate, against their townland address, in Pyke’s Survey of 1725 and Alsop’s Survey of 1765.

Bann Valley and Aghadowey was also home, from 1718, to that movement of Scots-Irish to New England, and this migration story, and the founding of Londonderry, New Hampshire, is told in this book in great detail.

Aghadowey was also famed in the 18th century for its bleach greens and the quality of its linen. As Rev. Mullin writes in Chapter 1 (p3) to gain insight into the 18th century origins of bleach greens and families involved in this industry: “I used the information obtainable in the Registry of Deeds in Dublin. In the research room, at the top of many flights of concrete stairs, I examined the lands index for deeds bearing on townlands where bleach greens existed. Where deeds were registered, they were looked up in the enormous dusty manuscript volumes in the research room, or their originals traced in the dim recesses in the vaults of the building.”

2) The Streets of Derry (1625-2001) by John G Bryson (Guildhall Press, Derry, 2001)

This book is my go-to reference book for Derry city. It identifies, in alphabetical order, the location, date of construction and derivation of street names of Derry city, including those of streets which no longer exist.

The gem, however, for those researching the origins of 17th century Derry city is simply titled, with no fuss or fanfare: ‘Appendix 4 – Lots of Feet, of Perches and of Acres.’ In this appendix John opened my eyes to the early days of the Plantation of the city of Londonderry.

The Charter of 1613 (which renamed Derry as Londonderry) obliged the Irish Society, a development corporation of the city of London, to build a walled town. By 1619 the city was completely enclosed within a stone wall, 24 feet high and 18 feet thick. The Irish Society laid out a town, within the walls, with about 300 house ‘lots’, each having a frontage of 36 feet, which John mapped as ‘the Lots of Feet’ in Map 1 (p201). In Map 2 (p202) of ‘the Lots of Perches’ and in Map 3 (p203) of ‘the City Acres’ John identified, respectively, the gardens and farms allocated outside the Walled City to the leaseholders who settled within the Walls.

In the original laying out of house ‘lots’ tenants were also allocated a garden of 34 perches (i.e. about one quarter of an acre) outside the walled city but still located on the island of Derry (i.e. that area bounded by the River Foyle and the Bogside) and a farm of 4 or 6 acres in size in the Liberties of Londonderry. Hence the occupiers of houses within the walls had a garden just outside the walls and a farm in the liberties surrounding Derry. Thus, in its early years the city of Londonderry was a farming enterprise as well as a centre of commerce and business.

Editor’s Note: Brian Mitchell is a professional geographer and the author of many distinguished books on tracing Irish ancestry. View Brian Mitchell Titles

His latest book is the New Pocket Guide to Irish Genealogy.