Federal Records of the Five Civilized Tribes

The following excerpt is from the book, Tracing Ancestors Among the Five Civilized Tribes, by Rachal Mills Lennon. This body of work has been the best-selling guide to a very difficult area of research for over a decade.

Ms. Lennon, M.A., CG, specializes in resolving difficult Southern research problems and reconstructing obscure lives, especially those of Native American, African American, and yeoman white families.

A Board-certified genealogist since 1985, Lennon holds degrees from the University of Virginia and the University of Alabama in architectural history, historic preservation and history, with emphasis on the Southern frontier. She is the author, editor, and compiler of six books, as well as award-winning problem-solving essays and case studies published in national-level peer-reviewed journals.

Federal Records of the Five Civilized Tribes

Historical Background

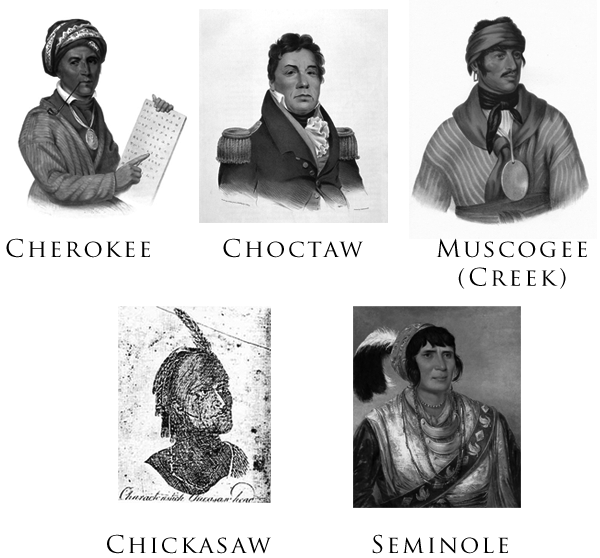

The history and culture of the American South are unique, owing chiefly to the intermingling of the races and the diverse ethnic backgrounds of countless families. Modern Southerners proudly boast traditions–real or not–of Native American ancestry. Odds are, these traditions lead directly back to the so-called Five Civilized Tribes. The Chickasaw, Cherokee, Choctaw, Creek, and Seminole Indians dominated a broad swath of territory from North Carolina to Mississippi before their forced removal westward. Long hailed for their adaptability to “white” ways (hence the designation “civilized”), these nations have gained near honorific status among Southeastern genealogists.

The five Indian groups that dominated the Southeast, known to history as the Five Civilized Tribes, were not all of the same ethnic family. The Cherokee were the southernmost branch of the Iroquois. Choctaws, Chickasaws, Creeks, and Seminoles were dominant members of the Muskogean family. Beyond these, several other tribes were still viable in the Lower South as the U.S. government moved into and across that area–for example, the Catawba in South Carolina and the Koasati (Coushatta) in Alabama–although federal records of the late-18th and 19th centuries largely ignore these smaller groups.

In Arkansas and Louisiana, states normally considered part of the Southeastern U.S., other tribes were active. However, the major groups there (the Caddo and Osage) were culturally akin to the tribes of the Southwest and the Plains. Smaller groups–remnants of the Attakapas, Chitimachas, Taensa, and Tunica, for example–had exceedingly limited relations with the U.S. until the 20th century; thus, little is found on them in the earlier federal records. However, by the time the U.S. had acquired this area, via the Louisiana Purchase of 1803, small bands from the Five Civilized Tribes were already migrating into Arkansas and Louisiana, first to hunt and then to settle.

Federal relations with America’s native peoples were both paternalistic and antagonistic. Consequently, the surviving historical records were kept for a variety of purposes: to subdue and subjugate tribes; to effect and maintain treaties; to minimize conflict between Indians and whites (and blacks); to acquire territory; to identify and compensate individual Indians and white countrymen displaced by land transfers; to remove tribes; to educate and assimilate individuals; and, of course, to financially support whole groups after they were reduced to welfare status by Euro-American encroachment.

Chronological Framework of Federal Records

Premodern records of federal interaction with American Indians are divided broadly into three bureaucratic periods. A basic familiarity with these political time divisions is essential to the location of federal records.

1774-1789: Pre-Federal Era:

September 1774 saw the first assembly of the Continental Congress, a body that would govern until the individual colonies adopted the Articles of Confederation in 1781. From then until the creation of the U.S. in 1789, the union was governed by Confederation congresses, which created three separate Indian superintendencies to serve the Southern, Middle, and Northern tribes. The records of this era are maintained separately froth the federal records below.

1789-1824: War Department Era:

With the creation of the U.S. in 1789, Indian affairs were assigned to the Department of War, where authority would remain for the next 35 years. Most records in the War Department were destroyed by fire on 8 November 1800. Consequently, for genealogical purposes, most “Indian records” within this department date only from 1800 to 1824. In 1806, an Office of Indian Trade was established within the War Department–a bureaucratic move that caused another regrouping of records.

1824-1947: Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) Era:

In March 1824, the War Department established a separate Office (later Bureau) of Indian Affairs–generally known today as the BIA. This office functioned until 1849, when it was moved to the Department of the Interior.

Hence, those “Indian records” genealogists seek at the National Archives are scattered across several collections, according to time frame: i.e., the records of the Continental Congress, the War Department, and the BIA. Most extant records of the Continental Congress have been published in print or microform, with excellent indexes. For the War Department era, resources are more limited and far less easily explored. Under the BIA, vast resources have been created, and major ones now have finding aids and published transcripts or abstracts. Yet many researchers who use them to search for Southeastern Indian forebears are disappointed because the BIA materials on these tribes predominantly relate to families that removed to Oklahoma.

Editors note:

From this point in her book, Ms. Lennon proceeds to describe the salient federal records along topical and tribal lines, creating a highly focused catalogue of the federal holdings that are most helpful for studying the Southeastern Indians who did not migrate westward. Readers can avail themselves of her fine detailed presentation of the records in Tracing Ancestors Among the Five Civilized Tribes: Southeastern Indians Prior to Removal.

Of related interest . . .

History of the Cherokee Indians and Their Legends and Folklore

Emmet Starr’s work is the classic account of the early Cherokees, their constitution, treaties with the federal government, land transactions, school system, migration and resettlement, committees, councils and officials, religion, language and culture, and a host of other topics. More than half of the book is devoted to genealogies and biographies, of which there are several hundred. The biographies in particular–each averaging a paragraph or more–are noteworthy for their focus on the genealogical events of birth, marriage, and death over a period of several generations. View In Store Now

Unlike Emmet Starr’s history, above, Myra Gormley’s delightful CHEROKEE CONNECTIONS provides a brief overview of extant genealogical sources pertaining to the Cherokee nation. It is designed specifically for researchers who are trying to prove their heritage for tribal membership as well as for those who are simply interested in investigating family legends about Cherokee ancestry. All important sources of genealogical value are explained with respect to the reasons why the various records were generated and where they can be accessed today. View In Store Now

Genealogy at a Glance: Cherokee Genealogy Research

Designed to cover the basic elements of research in just four pages, Myra Gormley’s Genealogy at a Glance: Cherokee Genealogy Research attempts to give you as much useful information in the space allotted as you’ll ever need. It provides an overview of the facts you need to know in order to begin and proceed successfully with your research, including Cherokee history, surnames, migrations, and basic genealogical resources, describing original documents as well as the latest online resources. View In Store Now