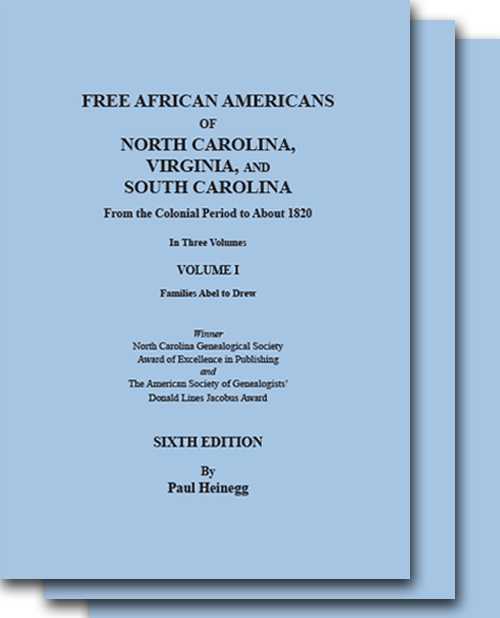

Interview with Paul Heinegg, Author of the New 6th Edition of Free African Americans of North Carolina, Virginia & South Carolina from the Colonial Period to About 1820 (Part Two)

Part One of this interview appeared in previous issue of Genealogy Pointers. It explores how the author first became interested in African American genealogy and his methodology. Part Two focuses on the major findings of Mr. Heinegg’s new 6th edition and the sources consulted, many of which are now available online.

Genealogy Pointers: You have devoted nearly four decades to this project. Given all the changes in genealogy and technology since you began, if you were starting from scratch today, how much time would you need to get to the Sixth Edition?

Paul Heinegg: It’s difficult to estimate the time it would take me to do this if starting from scratch. I spent a lot of time finding my way around the records. All research builds on former research. Knowing what I know now, I would avoid a lot of wasted effort.

The Family History group in Utah’s placement of all the Virginia and North Carolina county court records, deeds, wills, tax records, church records, N.C. Revolutionary War pay vouchers, etc., on Internet accessible files would certainly take many years off the work. And the Library of Virginia and N.C. State Archives have placed lots of their records on the Internet. And, of course, ancestry.com, fold3.com and other such sites have made all the census and Revolutionary War records available.

Internet access to all these documents means, not only that there’s no need to travel to the archives and research only during library hours, but one can at a moment’s notice go back and check a document. (Notice that someone is not in a particular Virginia county tax list in the 1780s where you expected? Just look in all the adjoining counties. Or maybe he’s just across the state line in North Carolina. Takes maybe 15 minutes on the computer.) Many times you go through decades of court records, then go through a tax record and find that the family name you’ve been seeing (and thought was a white family) was African American.

GP: You cover this in considerable detail in your Introduction, but can you boil down for us the major findings of your work?

PH: That most free black people who originated in Virginia’s colonial period would descend from white women was determined by the colonial legislature when it passed a law in 1662 which stated that a child’s status was determined by the status of the child’s mother. The child of a slave was a slave, and the child of a free woman was free. Although a number of slaves were emancipated in the seventeenth century, a law of 1723 all but eliminated emancipation of slaves in Virginia.

The colonial court records read something like a local newspaper. In addition to settling legal questions, the courts were charged with regulating the morals of the county. So, one gets a fairly good idea of what life was like for most people–as opposed to what one would read in a history book which, by necessity, must concentrate on the major personalities and events in our history.

The court records show how the institution of slavery developed in the colony. There were no slave quarters for the first slaves to go to in the 17th-century. And the slaves did not immediately develop a culture. That would only come when there were enough slaves in the same area to form a community. Before that happened, they worked with, slept with, got drunk with, and stole hogs with white servants. Their common enemies were their masters. One can see in the court records how racism developed to defend slavery rather than slavery developing from racism.

The great historian Edmund Morgan’s book from the 1970s, AMERICAN SLAVERY-AMERICAN FREEDOM, is very applicable now. His theory was that after Bacon’s Rebellion, Governor Berkeley and the other planters (who saw the lower classes as a completely different people from them) realized that they needed to make slaves into the lower class (or caste?) They convinced the poor whites that, poor as they might be, they were still white, free and above the slaves. Slaves could own property before (?) the Rebellion, but the governor took it away and gave it to the poor whites.

Bacon’s Rebellion in the 17th century is what made the U.S. different from England–no class system here. I saw first-hand in Saudi Arabia how they did the same thing. Hire foreign workers to do the dirty work, then all Saudis are on the same level–or think they are–even if a few are billionaires. “Never mind, we Saudis are all equal.” (Low level workers would think nothing of walking into the Saudi V.P’s office to complain.)

GP: Are there other new emphases?

PH: Another point I stress in the Introduction to the 6th edition has to do with the law binding the children of white women by men of African descent until the age of thirty-one. That law applied to their daughters and granddaughters as well. This law had a far greater impact on women than men. When a man completed his indenture, he had the skills needed to earn a living in a trade or as a farmer—-even if his most productive years were behind him. Women who were bound out until the age of thirty-one were likely to have children during their indenture. Each child added another five years to their service, in many cases making them servants for life and tying them to the slave population.

Gideon Gibson, an apprenticed son of Elizabeth Chavis in 1672, had descendants who attended Yale University (as whites) in the 1850s [Sharfstein, The Invisible Line, 54-6]. Many of the apprenticed descendants of his relative Jane Gibson were illegally held as slaves for most of the eighteenth century. Thirteen successfully sued for their freedom in 1792 and 1795, but the others were enslaved for life [See the Evans family history].

Jane Webb, the daughter of a white woman by a slave, sold her service to her master for seven years in exchange for permission to marry her master’s slave in Northampton County, Virginia. Her son Daniel Webb was a “free Negro” landowner in New Hanover County, North Carolina, in 1765 and left a New Hanover County will in 1769 [DB E:274].

One of Daniel’s sisters, Ann Webb, married a slave named Weeks and they were the ancestors of the Weeks family of Northampton County. Another sister, Elizabeth, sold her service to her master for sixteen years in exchange for marrying a slave Ezekiel Moses, and they were the ancestors of the Moses family of Northampton County. Still another sister Dinah married Gabriel Manly, the “Mulatto” son of a white woman in Northampton County. They moved to Norfolk County by 1735, soon after the completion of his thirty-one-year indenture, and were landowners in Bertie County, North Carolina, by 1742.

Jacob Chavis, a free-born “Black” man, owned over 1,000 acres of land and two slaves in Mecklenburg County, Virginia, by 1774. His relative Sarah Chavis left a Charlotte County, Virginia will in 1811 asking her executors to free her husband [WB 3:184].

William Chavis of Granville County, North Carolina, also owned over 1,000 acres of land and a number of slaves. And the county allowed him a license to operate an inn frequented by whites. One of his customers had his money stolen by another customer. Asked to testify for him in court, Chavis responded, “I am a Black man & don’t care to undertake such a thing.”

This latest edition incorporates the Library of Virginia’s digital chancery case files as well. Among them is another family history which illustrates the different circumstances of male and female free African Americans.

Jane Gibson, a relative of the above-named Gideon Gibson, had a “dark Mulatto” daughter named Jane who married Morris Evans, a “Mulatto” man who died in York County in 1742. Their sons were landowners in Mecklenburg County, Virginia, but many descendants of their daughter Frances were held as slaves, some until they sued for their freedom in 1795 and others until Emancipation. This story was revealed in a Library of Virginia chancery case in which an 81-year-old Robert Wills testified in 1791 about events in colonial Charles City County, which is a burned-record county.

Asked if there were any other free familes descended from Jane, Wills testified that her descendants included the free Scott, Bradby, Smith, Redcross, and Morris families of Charles City County and the Bowman family of Chesterfield County, “many of them are black, some nearly white and others free mulattoes…from a promiscuous intercourse with different colours [Lynchburg City chancery file, 1821-033, Library of Virginia digital site].

Rachel Alford, a “free Christian white woman,” was living in Fauquier County, Virginia in 1769 when the court ordered the churchwardens to bind her “Mulatto” son Gge as an apprentice. We know who her husband was because she bought him from his master and set him free, according to a Fauquier County deed in 1795.

John Day, a “man of color,” enlisted in the Revolution in Granville County in 1777 and died at Valley Forge in 1778. His brother Jesse Day authorized an attorney to collect a warrant for 640 acres for John’s service, but the attorney stole the money. Jesse’s heirs sued and won their case against him in 1830.

Some court records which would record the origin of families have not survived. However, the papers which counties used to authorize their free Negro registers have been published recently on the Library of Virginia’s African American Narrative Digital Collection.

When Easter Atkinson registered in Fredericksburg, elderly residents of King George and Fauquier counties recounted how she was the daughter of Mildred Atkinson, a “Mulatto” woman who was the daughter of Easter Atkinson, a white woman from Fauquier County.

Most early court records for Henrico and Chesterfield counties have survived, but the courts did not record the origin of the free Ligon family. That is detailed in the documents filed for the registration of Jeremiah Ligon (who served in the Revolution). The papers contain the testimony of a man who stated in 1800 that he had known the family for the past 40 years. Jeremiah’s father William Ligon was a free “Mulatto” and his mother Hannah a free “Black woman” who had both served apprenticeships in Chesterfield County.

Ephraim Hearn of Gloucester County, who served in the First Virginia Regiment, was taken prisoner in Charleston in 1780 and was placed aboard a prison ship until the general prisoner exchange in 1781. He was described as a “free mulatto soldier” in the Virginia Gazette. The colonial court records for Gloucester County have not survived, but the register of Abingdon Parish records the birth of Ephraim and two other children of a “Mulatto” woman named Jane Hern.

The Jacobs family was freed by the will of their master in Northampton County, Virginia, in 1700. They were in North Carolina by 1745. Thirteen members of the family owned land in New Hanover County, and seven served in the Revolution.

Six members of the Tann family served in the Revolution and 3 were among more than 30 free African Americans from North Carolina and Virginia who died in the service.

GP: What were some of the surprises that came with the research?

PH: The first surprises were that:

Some of my wife’s family were free before Emancipation

That many families in her home county of Northampton, N.C., and adjoining Halifax County owned their own land before 1800.

That they made up about 10% of the free population of those counties in 1800 and about 12% in 1810.

That was about 10 times the population of “other free” persons in many other N.C. counties.

The white population of those counties must have made them feel welcome.We can only speculate why. (This was all the more surprising since the area was completely segregated in 1987 when we visited for a family reunion.)

I was later to learn through my research that this area of N.C. was considered the frontier in the 1720s when a number of free African American families owned land there. Perhaps the children and grandchildren of their white neighbors had grown accustomed to having free African American neighbors?

New settlements welcome new settlers, so they can reach an economy of scale–to get their goods to market, etc.

This all changed in the 1830s after Nat Turner’s Rebellion and other developments detailed by historian John Hope Franklin. In the decades before the Civil War free African Americans were told in no uncertain terms (the free Negro codes) that they were no longer welcome and many moved West.

Another interesting finding pertained to special schools for free blacks. During Reconstruction, the South set up separate school systems in each county: white and “colored.” This meant that the former “free colored” population would attend school with the former slaves. While the former “free colored” population bore no particular animosity toward the former slaves, and some were married to former slaves, they objected to being classed with people who had been considered property and were still considered someone’s former property rather than people. Attending school with former slaves meant a considerable loss of status for them.

The Democratic Party (Dixiecrats) in North Carolina took advantage of this by allowing the former “free colored” population in Robeson County to set up their own separate schools in exchange for their votes to pass legislation to make North Carolina a Jim Crow state. The head of the Democratic Party in the county needed an excuse, so he called the third school system “Croatan Indian” after a popular legend at the time that Sir Walter Raleigh’s lost colony in 1587 on Roanoke Island off the North Carolina coast wasn’t actually lost. The colonists (instead of being killed by the Indians as were the colonists in the former attempt at a colony there) met up with friendly Indians with whom they mixed and were the ancestors of the former “free persons of color” of Robeson County. (The white residents knew this to be a made-up story and called them the pejorative “Cros” after Jim Crow.)

However, anthropologists saw an opportunity to make a name for themselves or were fooled and set about finding lost Indian tribes among all the former “free person of color” communities in Delaware, Maryland, North Carolina and South Carolina where they named the groups after the last Indian tribe to have inhabited the place. (Anthropology was not then the discipline it is today.)

Many of those communities adopted an Indian identity which, after many generations, is as real to them today as it would be for a person who was an Indian.

And this interpretation is favored by many in the general population, perhaps because it means the United States did not really annihilate all those Indians. We allowed some to remain and live among us.

The fact that the communities owned land, had a different culture from slaves, and generally had lighter skin color than most slaves were arguments enough for many.

These beliefs/ culture remain with us today and obscure the true history of these free African American communities.

Recent Blog Posts