Origins and Descendants of White Slave Children of Colonial Maryland and Virginia

Editor’s Note: The following post is written by Genealogical Publishing Company author Dr. Richard Hayes Phillips. His books tread into territory that has been previously underreported, colonial white slave children. In his post below, Dr. Phillips discussing some of his research efforts that went into the making of White Slave Children of Colonial Maryland and Virginia: Birth and Shipping Records, as well as the reasons behind writing this book.

The Genealogist as Detective: Richard Hayes Phillips and the Search for the Origins and Descendants of White Slave Children of Colonial Maryland and Virginia

Some time ago I published a book — Without Indentures: Index to White Slave Children in Colonial Court Records — in which are identified, by name, 5290 “servants” without indentures, transported without their consent, against their will, to the Chesapeake Bay, and sentenced to slavery by the County Courts of colonial Maryland and Virginia. The younger the child, the longer the sentence. These were white kids, with surnames different from those of their masters.

I wanted to know where these kids came from, and so did everyone I talked to on the other side of the Atlantic Ocean. I did have clues to work with. Most of the surnames were English, and there were many Irish and Scottish surnames also. Some of these kids identified the name of the ship that transported them, which in some cases, for example, the Sarah of Bristoll, suggested a port of departure. And I knew their ages, or nearly so, as adjudged by the County Courts on a date certain, from which I could figure out the approximate years of their births.

What I really needed was shipping records. If I knew for certain the ports of departure of the white slave ships, I would know the shires and counties from which these kids were taken. Then I could do a targeted search of the birth and baptismal records. I would not be able to distinguish among children with a common name, like John Smith or Mary Jones. But if the names were unusual enough to appear only once in the right time frame in any of these places, I could match up the children with their parents. Among all the early settlers of Maryland and Virginia, these hapless, abused, discarded and forgotten children are the easiest to trace back to their homelands, because we know their ages.

I visited eleven public record offices overseas to look for shipping records. I did find records for Bristol ships covering the period from 1654 to 1691, and for Liverpool ships from 1697 to 1707, but almost no records for London ships, and very few records for the peak years of child trafficking, 1698 to 1701.

The breakthrough came at the Library of Congress. There staff brought me five thick file folders stuffed with photostatic copies, negative images on card stock, of original handwritten shipping records from Maryland, 1689 to 1702. These photostats were provided by the Public Record Office of London in 1939. Nobody at the Library of Congress knew that they had these records. The State House at Annapolis, Maryland was destroyed by fire in 1704, and the original shipping records were lost in the fire, but the British wanted everything in triplicate, and the handwritten copies sent to London have survived.

These are shipping records, not passenger lists. The kids are identified not by name, but as “white servants,” or “European servants,” and are listed as “cargo,” along with the rum and tobacco, or as items requiring the payment of import duties, two and a half shillings per head, to the Royal Naval Officers of Their Majesties William and Mary. And these were not all London ships. Ports of departure for white slave ships included Belfast, Bideford, Bristol, Cork, Derry, Dublin, Falmouth, Liverpool, Newcastle, Plymouth, and Whitehaven. Among the owners of white slave ships were a Mayor of Bristol, a Mayor of Bideford, and a Governor of Virginia. Shipping records for 170 white slave ships are abstracted and collated in the book.

Now I was ready to search the birth and baptismal records. I began with the records that had been transcribed, indexed, and posted on the internet, or otherwise published. Some of the surviving records were not found for the time period in question (c. 1640-1700), so I traveled to Belfast, Whitehaven, Bristol, and Exeter to examine transcriptions or microfiche copies of the missing records. This completed my data set for every major port of departure except Gravesend, the Port of London. It is beyond the capability of one historian to collect and examine all the baptismal records for London, Kent, and Essex. There were too many people living there at the time, so I had to settle for what is online.

Altogether, I was able to match more than 1400 children with the parish or town records, their names appearing only once in the right time frame. The kids were taken from England, Scotland, Ireland, and Massachusetts.

Kids who were shanghaied from Massachusetts, if they survived their servitude, could go home. They could walk if they had to, and some of them did. Twenty-eight of them appear in the Town Records of Massachusetts as grown adults, after their expected date of freedom, and in twenty cases their families can be traced forward to the Revolution. Among their direct male descendants, and husbands of direct female descendants, are 205 confirmed veterans of the American Revolution, including 72 minutemen, active on day one, 19 April 1775, at Lexington, Concord, Cambridge, or Boston.

All of this, and more, can be found in my new book — White Slave Children of Colonial Maryland and Virginia: Birth and Shipping Records.

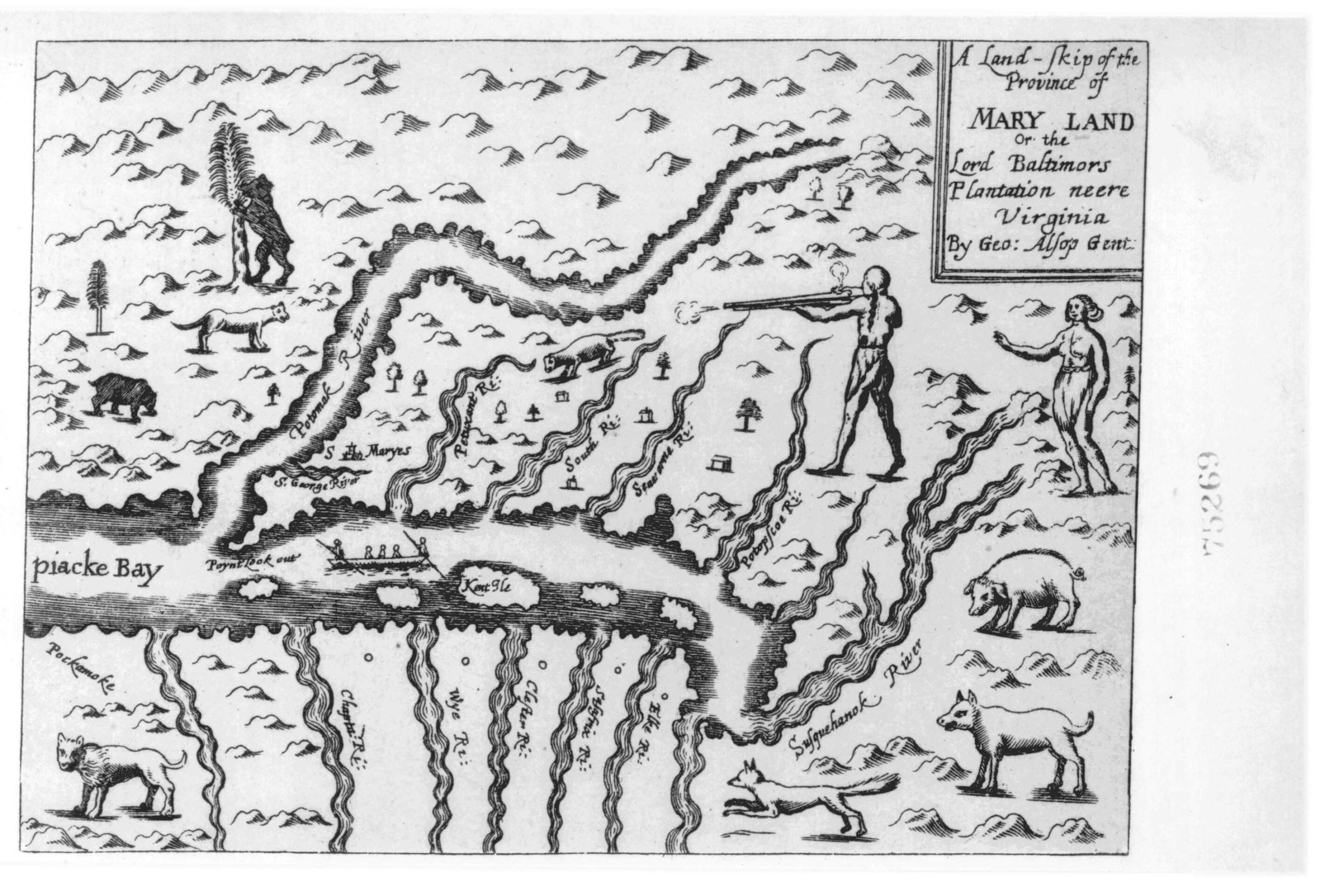

Image credit: Map of Colonial Maryland from: George Alsop, A land-Skip of the Province of Mary land, 1666 [1869], in Gowan’s Bibliotheca Americana, via Wikimedia Commons