As the genealogist of a Scottish clan organization, I have for many years been frustrated by the notion of a “family coat of arms” and even more frustrated by the sale of such contrivances at Scottish and Celtic games and festivals where the organizers should know better. I strongly believe that you should be knowledgeable about your heritage and observe its uses appropriately. So I will start out by saying very clearly – There is no such thing as a family coat-of-arms. A coat-of-arms belongs to an individual, and only to that individual. Having gotten that off my chest, let me step down from my soap box and provide some background on heraldry and some details about a coat-of-arms. Given my interests and experience, this information will focus on Scottish and English arms and will of necessity be selective in its discussion.

The origin of coats of arms can be traced to armed conflict on the part of knights clad in suits of armor. Although the individual design of the helmet or the embellishments of other pieces of the armor might vary from knight to knight, looking out at a scene of battle with lots of men wearing armor, one would find it difficult to distinguish one from another, and more importantly, to know quickly who were the “good guys.” Each man, therefore, began to wear an identifying coat or tunic over his armor, hence, “coat of arms.” The identifying design and colors would also be displayed on his banner, shield, and the trappings for his horse. As time went on, this unique, individual design, began to appear on an individual’s clothing in his non-military life as well, and, because no two men in the same area wore exactly the same coat of arms, these symbols came to identify his belongings as well. The most important element became the shield bearing the design of the “arms” as it became the basis for heraldic devices as they evolved.

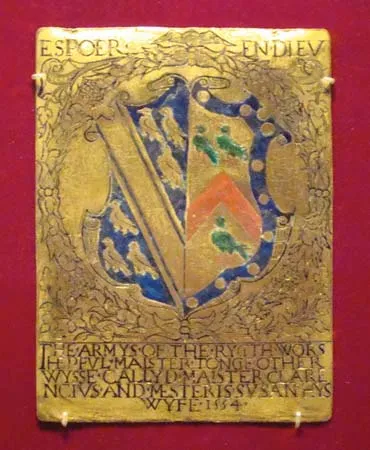

In addition to the coat itself, the knight wore a helmet on top of which began to appear his personal crest made either of light wood or boiled leather. Below that hung a mantle, usually made out of silk that covered his neck and protected it from the sun. It was held in place by a wreath of twisted silk. If the individual were of high rank, he would have a chapeau, crest or coronet instead of a wreath holding the mantling on his helmet. In depicting his arms, the helmet, crest and mantling appeared above the shield. A motto was then added (think of such things as “Aut agree aut mori,” “Either action or death”) and the depiction of all of these elements (shield, helmet, crest, mantling and motto) came to be form the basic heraldic device or “achievement” of a gentleman. Some more prominent individuals had their shields held up by “supporters” (think of the unicorn and lion of the British royal arms), standing on a mound, or “compartment.” Thus the full achievement of a peer is made up of his coat of arms, chapeau or coronet, helmet, crest, mantling, motto, supporters, and compartment. Such achievements are used today by individuals on banners over a house, on the side of cars, on stationary, furniture, china, etc. We also see coats of arms used by officials, colleges and universities, companies and corporate bodies, cities, etc.

An achievement belongs to an individual and is made up of elements unique to him or to historical or other events in his life. What about other members of his family? Heraldry is one area in which primogeniture still operates. An individual’s arms may be inherited by the eldest son in each generation. While that individual’s father is alive, however, the arms must be “labeled” with a special mark. Look at the coat of arms for the Prince of Wales and you will see that it includes a mark that looks like a thick, straight black line with three legs. This mark will be removed following the death of Queen Elizabeth and Charles’s assumption to the throne. At that time he will assume the “unlabeled” arms of the sovereign. Daughters are allowed to use their fathers’ coats of arms, but they are normally depicted on a diamond-shaped “lozenge.” When they marry, daughters can place their father’s coat beside their husbands’ shields in a depiction known as “impaling.” If they had no brothers, they then may place their own shield in the middle of their husband’s shield. Sons other than the first son still have the right to be armigers (those who have been granted coats of arms). Their arms are based on those of their father, but where the first son inherits the exact same arms as his father, younger sons have to make a permanent change to the basic design, known as “differencing,” to distinguish themselves from their eldest brother. To do this, a new color may be introduced or different “marks” or design elements such as borders may be added. The process can continue, denoting additional generations, family lines, heirs, heiresses marrying into the family, etc. and achievements can become quite complex. As a rule, only about six “quarterings,” or subdivisions, are shown.

How do individuals get coats of arms? In England, the College of Arms, and in Scotland, the Court of the Lord Lyon, have legal control over rights to arms. Assisting them are officers known as “heralds.” For English arms, an individual must be English or of English descent and be able to prove male descent (father to son) from someone whose coat is officially recorded at the College of Arms. Alternatively, if your ancestor was a British citizen (colonists prior to the Revolution), you may matriculate arms in that individual’s name. Apply to the Earl Marshal through the College of Arms for Letters Patent, providing well-documented genealogical information. Once this information is approved (and a hefty fee paid), the various elements of the coat of arms are designed (another hefty fee) and the arms are “matriculated.” In Scotland, you must apply to the Lord Lyon King of Arms in the Lord Lyon’s Court, and either be Scottish or of Scottish descent. Begin by documenting your descent from someone who has recorded arms in the Lyon Register in Edinburgh. Again, you will be required to submit substantive, genealogical proof.

A variety of colors and devices are available for a coat of arms. Only five colors are generally in use: red (gules), blue (azure), black (sable), green (vert), and purple (purpure). In addition, two metals, gold (or) and silver (argent), as well as furs such as ermine may be used. “Ordinaries” such as a cross, a chevron, a bar, a border, etc. can be added. Animals such as lions, often referred to as rampant or passant (walking) leopards (a lion looking directly at you), dolphins, eagles, griffins, etc., or roses and fluer-de-lys may be used. Other devices include the sun, a scallop shell, trefoils, arrows, sheaves of wheat, etc. often appear. Still other additions will indicate the individual’s place in society: the helm for royalty is gold with bars, for peers it is silver with gold bars, for knights it is steel with the visor open. Scots barons and chiefs display a tournament helm, and gentlemen, a steel helm with the visor closed.

The detail in such heraldic devices is amazing and I have learned in writing this unillustrated article that it is sometimes difficult to express clearly in writing such very visual images. Even here, heraldry has an answer. The term “blazoning” refers to the ability to describe a coat of arms in technical terms or to describe a complex image in words. A specific sequence is used, and an example might read “argent two barrulets (narrow bars) wavy azure, between in chief two maple leaves slipped and in base a thistle eradicated (uprooted) gules, a bordure sable charged with eight bezants.” While that might take a while to work through, an individual well versed in heraldry would be able to interpret all the separate parts, draw a close facsimile, and be able to identify to whom the arms belong (in this case Lord Beaverbrook).

Heraldry and the development and description of coats of arms is not only detailed, but very interesting. Clearly, “family coats-of-arms” are no more than pretty artwork, but that’s all. Arms are held by individuals and are personal to that individual. As such, they are protected by law, both in their design and in their use. As individuals of British Isles heritage, we need to understand and respect these laws and traditions.

A variety of titles are available for your further study:

- Fairbairn’s Book of Crests of the Families of Great Britain and Ireland by James Fairbairn

- The Clans, Septs and Regiments of the Scottish Highlands by Frank Adams

- An Ordinary of Arms: Contained in the Public Register of All Arms and Bearings in Scotland

- Scots Heraldry: A Practical Handbook on the Historical Principles and Modern Application of the Art and Science by Sir Thomas Innes 2nd rev, enl. ed.

- The Dictionary of Heraldry, Feudal Coats of Arms and Pedigrees by Joseph. 1902 (Studio Editions, 1994)

- The Complete Book of Heraldry: an International History of Heraldry and its Contemporary Uses by Stephen Slater (Hermes House, 2003)

- American & British Genealogy & Heraldry: A Selected List of Books by P. William Filby, 3rd ed. (Boston, NEHGS, 1985)

- Heraldry, Ancestry and Titles: Questions and Answers by L. G. Pine (Gramercy Pub. Co., 1965)