The following review appeared in the March 2022 issue of the National Genealogical Society Quarterly, pages 67-68

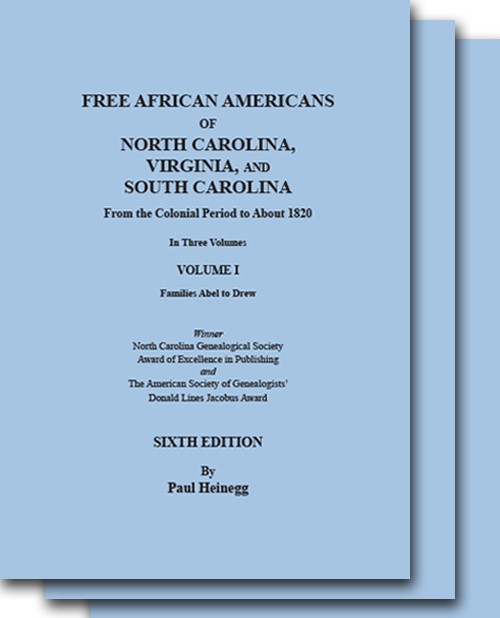

“Free African Americans of North Carolina, Virginia, and South Carolina from the Colonial Period to About 1820. 3 volumes. 6th edition. By Paul Heinegg. Published for Clearfield Company by Genealogical Publishing Company, Inc.; 3600 Clipper Mill Road; Suite 229; Baltimore, 21211-1953; http://www.genealogical.com/; 2021. Set ISBN 9780806359212. Paperback. $152. Volume 1. Families Abel to Drew. ISBN 9780806359229. xii, 566 pp. index, tables. Paperback. $54.95, Volume 2. Families Driggers to Month. ISBN 9780806359236. iv, 580 pp. Index. Paperback. $54.95. Volume 3. Families Moore to Young. ISBN 9780806359243. iv, 586 pp. Index, sources. Paperback. $54.95.

In the sixth edition of Free African Americans, Paul Heinegg offers several important updates to his decades of research. Over three volumes, he attempts to reconstruct the lines of hundreds of families with roots in colonial North Carolina, Virginia, and South Carolina. He assembles genealogies for well-known free families, such as the Chavis, Bass, and Gowen families, as well as many lesser-known families. These updated volumes include references to numerous digital resources only recently available online. Heinegg integrates these digital source references with his findings from books, microfilm, and original records. Free Negro registers, county court minutes, Revolutionary War pension records, wills, deeds, law books, petitions, tax records, and apprentice records are among the sources Heinegg cites.

Family historians will be excited to learn Heinegg’s work includes a forward by the late historian Ira Berlin and a detailed introduction, where he outlines his arguments and conclusions about the origins and daily lives of free people in the colonial period. He contends that most families he researched were descendants of white servant women. He explains that a smaller number descended from enslaved persons freed in the early colonial period. Furthermore, he asserts that “Free Indians blended into the free African American communities. They did not form their own separate communities” (vol. 1:1). Heinegg points to Virginia as the origin place for most of the families in his study. He dedicates several pages to explaining his reasoning for making each of these assertions.

The bulk of Free African Americans outlines the lineages of each free family. Some entries span multiple pages, including findings on the Dungee family, which runs six pages. Other genealogies are much shorter, such as the brief family trees of the Rowland and Rudd families, each less than a page. The quality of the evidence used to construct each family’s genealogy varies. In some cases, solid evidence supports connections between individuals with the same surname. In other cases, the connections Heinegg draws are simply hypotheses. His guesswork is sometimes qualified by the word “probably” or a question mark. Readers must ultimately decide whether to accept all of Heinegg’s interpretations and arguments. Regardless, the thousands of citations demonstrate a high level of dedication to his topic. This updated edition of Free African Americans will serve as an important resource for new researchers seeking information about their free ancestors. Other researchers who are simply interested in the lives of free people in the colonial period should also find the three-volume set enlightening.” – By Warren E. Milteer, Jr. Burlington, North Carolina