In the April 7 and 14 issues of “Genealogy Pointers,” we described two systems by which land was transferred by colonial authorities to individuals: The New England Model and the Colonial Government System of Land Transfer. As Patricia Law Hatcher explains in her definitive study of U.S. land records, first transfer varied both geographically and chronologically throughout the British colonies. This third installment of the land transfer process describes the transfer of parcels from large tracts owned by proprietors like Lord Baltimore. It is reprinted verbatim below, from pp. 73-75 of Pat Hatcher’s Locating Your Roots. Discovering Your Ancestors Using Land Records.

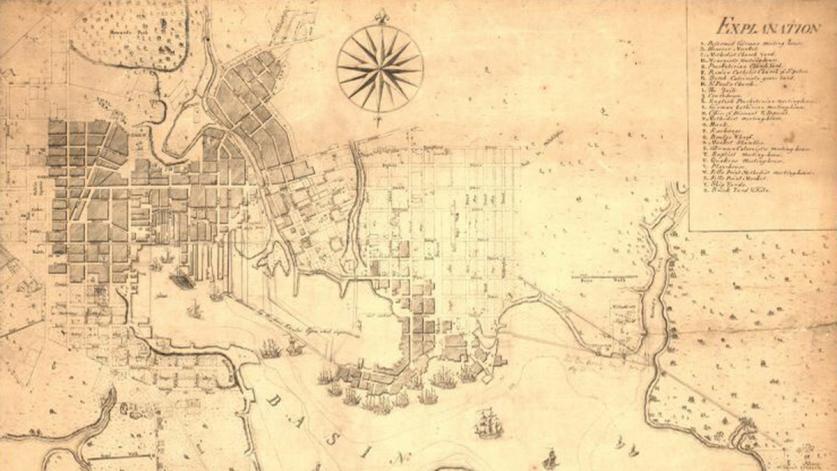

You probably remember reading in history class about Lord Baltimore and William Penn. The colonies of Maryland and Pennsylvania were direct grants to individuals, as was the Northern Neck of Virginia, granted to several proprietors but later associated with Lord Fairfax; the northern portion of North Carolina, granted to Earl Granville; and the Jersey proprietorships. In New York, proprietorships were usually referred to as manors (remember the feudal concept of landownership).

The land was, technically, the private property of the proprietor. He then sold parcels to individuals. Because he owned the land privately, the record of the transfer was private. However, in Maryland and Pennsylvania, the grants were enormous and soon became colonies, so a public record also is available, as is true with the Fairfax grants in Virginia.

There were smaller grants made to proprietors by the crown or by the administrators of the colony. In these cases, the transactions from proprietor to individual often were recorded as private records. Also, some proprietors, most notably in New York state, followed the European custom of renting or leasing the land, rather than selling it outright. These factors can be frustrating for genealogists. Some records, such as those for the Holland Land Company in New York and the Granville grants in North Carolina, are publicly available. Others, such as those for the Otego Patent, also in New York, aren’t public and quite possibly don’t survive.

The close of the Revolution brought concern to the many landholders who held their land by a right from a proprietorship, which usually held its authority from the crown. However, in almost all cases, states recognized that established settlement was a positive thing and accepted these landholders as the valid landowners.

Because recording a deed was at the option of the buyer, some cautious buyers had their patents recorded. More often, you’ll find the grant mentioned in the chain of title when the first individual owner sold the land.

Look at the deed for Edward Halsey (spelling does not seem to have been the scribe’s strong point).

“This Indenture made the twenty seventh day of September in the year of our Lord one thousand seven hundred and ninety 1790 between Edward Halsey of Otego Osago Township Montgomery County and State of New York and Hannah his wife of one part and Thomas Cartwright late of Var- mont now of Otego in County and State afsd of the other part…”

Notice that even the opening of the deed provides helpful information–the given name of Edward’s wife (the only place this is ever mentioned) and, for Cartwright descendants, Thomas’s state of origin.

“one hundred acres strict measure . . . which piece of Land is part of one thousand acres formerly belong to Samuel Alison which part was given unto the sd Edward Halsey and the same conve’d by Deed of Lece and Relece breeing date the seventeenth day of March one thousand seven hundred and seventy five, the same is a part of sixty nine thousand acres formerly granted unto the sd Saml Alison by Thomas Wharton of the City of Phildelphia on the third day of Feabruary 1770 as by the sd patent record in the Secritarys Offics at New York in Libro Number 14 of Patents 535 which may appear by the former grants, and the sd SamlAlison by Deed of Leace and Releace to the said Edward Halsey his heirs and assigns, and the Lot hereby granted is a part of Lot No. 39.”

The deed mentions Edward Halsey’s 1775 grant as part of the chain of title, a section often found in deeds. Unfortunately, this 1775 grant does not appear to have been recorded.

It took some digging to figure out what those early records referred to (as has been mentioned, land records can contain confusing elements), but the investigation proved useful to learning more about Edward Halsey’s life. Samuel Alinson was one of sixty-nine proprietors who patented sixty-nine thousand acres as the Otego patent. They took approximately one thousand acres each.

The grant to the proprietors had an interesting quirk (fortunately, I didn’t have to read the New York patents; I found it printed in a book). The proprietors would lose the land unless

“. . . within three years next after the date of this our present grant [3 February 1770] settle on the said tract of land hereby granted, so many Families as shall amount to one Family for every thousand Acres . . . also within three years plant and effectually cultivate at the least three Acres for every fifty Acres … capable of cultivation …”

Restrictions such as these were not uncommon in areas where the goal was getting inhabitants onto the land (often with the unstated intentions of pushing the Indians farther west and serving as a buffer). A single element of the metes and-bounds description in Edward’s deed tells us that he was one of those earliest settlers fulfilling that requirement and that he had lived in Otego two years before the date of his patent.

“ . . . beginning at Beach tree by the west side of Otego Creek now dead and fallen down on Lot number 39 & 40 thence runing west fifty chain to a maple marked on three sides, then north twelve degrees East twenty chain to a stak formley set up for a corner, thence East fifty chain to a Hemlock standing on the bank of Oreo [sic] Creek marked thus E. H. 1773 thence down sd Creek to the place of beginning . . .”

Some proprietorships first had the land surveyed into lots and then sold the land on a lot -by-lot basis. In the Otego patent above, each proprietor got a numbered lot, but how he divided that lot was his business.

Most proprietors, however, sold land described by metes and bounds. The individual chose the exact boundaries of the land he wished to obtain, and a survey was then done (the indiscriminate-survey system). The title transferred via patent, grant, or other instrument according to the survey description.