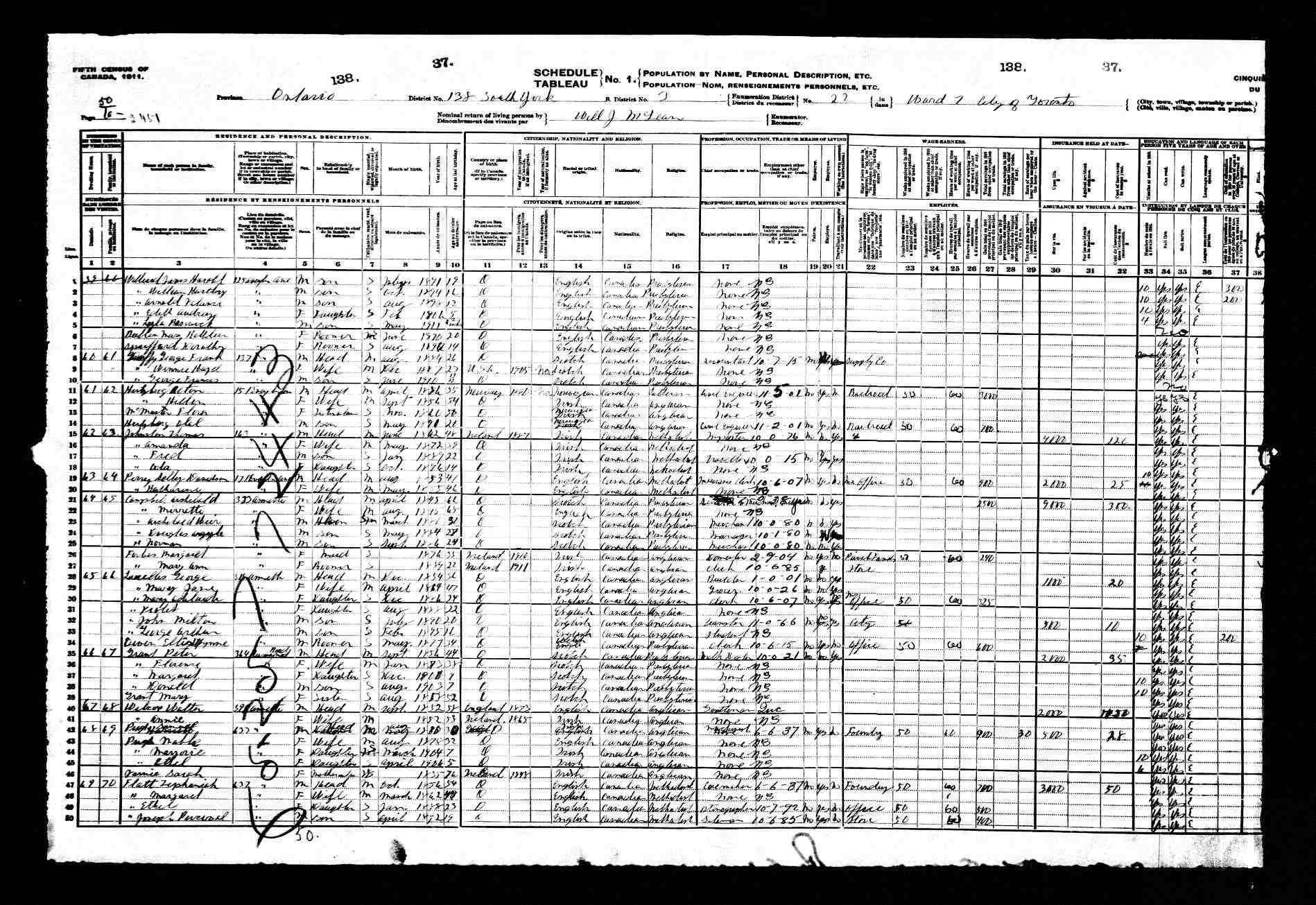

The following post is from author, Denise Larson, who has offered her expertise on other topics such as Maine Genealogy in two parts, as well as the recently posted piece about Canada’s upcoming anniversaries (from 2016).

This year, 2016, marks the sesquarcentennial—350th anniversary—of the first official census taken in Canada. Only 163 pages long and enumerated in part by Intendant Jean Talon himself, the census of 1666 noted the name, age, and occupation of the French inhabitants of Quebec City, Montreal, and Trois Rivieres. In this post, Ms. Larson discusses the evolution of the census in Canada as well as some tips for researchers to keep in mind.

Enumeration can be more than general population

From that simple start in 1666, census taking in Canada expanded to Acadia in 1671. Canadian population censuses are either nominal, listing all members of a household, or partly nominal, listing the heads of household. Beginning in 1851, a listing of all family members became standard in Canada.

Some enumerations were very specific to a certain civil or religious group. In 1765 a census was taken of the Protestant inhabitants in the District of Montreal. A year later the merchants of Montreal were enumerated. A census taken in 1779 surveyed the Loyalists who fled the American colonies to the south, settled in the Province of Quebec, and received provisions from the British government to compensate for their losses. This type of census has proven to be very valuable to family historians who traced ancestors to early colonies but abruptly lost the trail during the turmoil of the American Revolution.

Library and Archives Canada offers a list of extant Canadian censuses on its website at http://www.bac-lac.gc.ca/eng/census/Pages/census.aspx. The page lists the years of census returns, a finding aid, and searchable databases.

Not everything is as it appears in Canadian census records

The Library’s Finding Aid Number 300 warns of some pitfalls adherent in Canadian census returns. Users are cautioned that the source of the information written onto a census form might have been a neighbor, not a family member. Even if the information was correct, the spelling skill of the enumerator might be cause for confusion.

The native language of the person taking a census in Canada might be a factor in the correctness of the return. An enumerator whose first language was not French might record “Salway” for Saint Louis, which could have been pronounced something like “san louie” or “san-lou-eh.”

The personal creativity of an enumerator might cause misunderstandings in reading his notes if he used the abbreviation BC, meaning Bas Canada (Lower Canada) if it were misunderstood to be British Columbia and transcribed as such in an index.

The specific age of an enumerated person can sometimes be difficult to determine from a census return. Is the given age how old the person was on the actual date of enumeration (sometimes shown at the top of the page); or how old he or she would be on his or her next birthday; or is the age given as of the “census day,” the date specified for that particular census on which all information was supposed to be based? Some censuses were started in one year but completed the next, which could throw off a calculation. Researchers should apply a grain of salt to a recorded age and look for proof positive in other sources.

Census taking is not an exact science, but the information recorded by hard working enumerators is a valuable starting point from which to launch a search for firm evidence about family names, ages, occupation, and location on a certain date — the basis used in the Canadian census of 1666 and censuses thereafter.

Image credit: 1911 Canadian Census – Archibald Campbell household, care of Howell Family Genealogy Pages.