(The following article was excerpted from Chapter 7 of Sustainable Genealogy, entitled “Military Service of Ancestors.”)

“When I hear of some of the wildly exaggerated claims of the military exploits of my own ancestors and anyone else’s, I am reminded of “The Battle of Mayberry” episode of the Andy Griffith Show. In one episode, Opie’s class was assigned to write an essay about the so-called “Battle of Mayberry” which had involved the early settlers of the town of Mayberry and the Native American population two centuries earlier. Andy and Aunt Bea immediately told Opie about his own ancestor, Colonel Carlton Taylor who, by their account, played a leading role in the battle. Opie then went on to talk to all of the major characters in the town . . . [who] all told stories about ancestors who held the rank of “Colonel” at the time of the battle. All of them described the settlers winning the battle with only fifty armed men facing 500 Native Americans. Andy, realizing Opie’s confusion over the conflicting accounts, took him to visit a local Native American named Tom Strongbow . . . who told of his own ancestor, Chief Strongbow, leading fifty warriors to a victory over 500 armed settlers. . . . Finally, Andy took Opie to Raleigh, North Carolina, the state capital, to give him an opportunity to look up contemporary accounts of the battle. What Opie found was a newspaper account that told of a dispute that started over a cow accidentally killed by a Native American in Mayberry. Instead of fighting a battle though, fifty settlers and fifty braves settled the dispute by sharing several jugs of liquor and killing some deer to compensate the owner of the cow.

From Private to Major

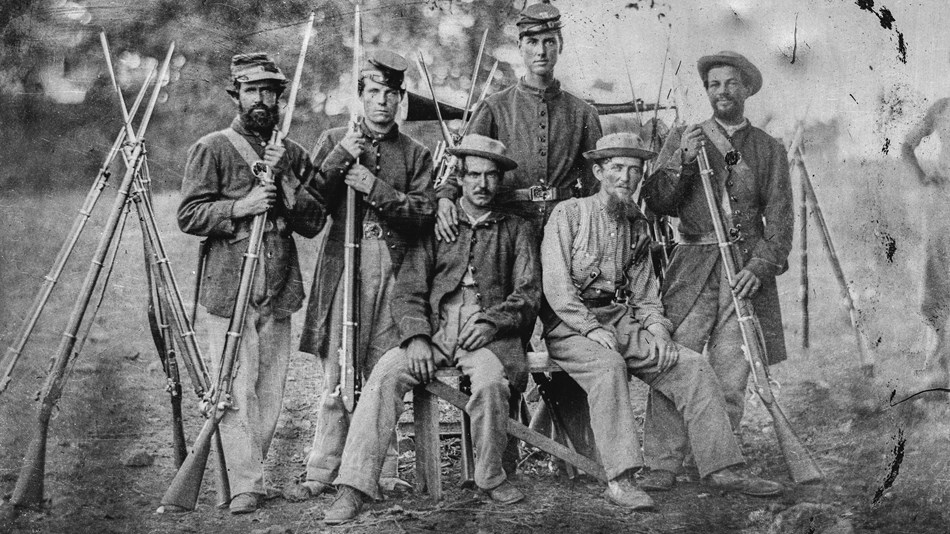

That whole story is, of course, fictitious but exaggerated accounts of ancestors’ military exploits are a dime a dozen in oral history whether “truly oral” or “written oral.” One of the most common mistakes is an inflated rank assigned to an ancestor. A likely source of this, particularly for Civil War soldiers, stems from the late 19th and early 20th century habit of referring to elderly veterans of that war as “Colonel” or “Major” – even for those that never rose above the rank of private. This was most common for Confederate veterans, but Union veterans were also referred to by these honorary titles in some instances. It is easy for overeager descendants who hear an ancestor referred to by an honorary rank to jump to the conclusion that he actually did hold such a rank while in the service. Usually, these claims of such high rank are relatively easy to check, especially for Civil War soldiers. Records for soldiers in earlier wars are not so voluminous but there are many, nonetheless. Service records and pension applications give the ranks soldiers achieved and it is not at all unusual to learn that an honorary major never actually rose above the rank of private. In the case of common names, proof (or disproof) may be a bit more of a challenge. A descendant of a private named John Smith will undoubtedly have little trouble finding a colonel or a major with that rank in some regiment from the state their own ancestor served from. In this kind of a case, researchers should examine the economic circumstances of the ancestors, before and after the war. Assuming that a man named John Smith, who owned less than fifty dollars’ worth of real estate at the time of the 1860 and 1870 census enumerations, held the rank of “Colonel” during the Civil War is not a leap of faith I would make.

The General’s Right Hand Man…

Sometimes the stories of ancestral military exploits are more specific than an overinflated rank. One of the Pennsylvania German families I descend from is a family named Ickes. In the late 1990s, I was searching for information on them on Genforum.com, which was the primary means of exchanging genealogical information on the Internet at the time. I came across an account posted by a descendant of Nicholas Ickes (1764-1848), the founder of the town of Ickesburg in Perry County, Pennsylvania. Nicholas is not a direct ancestor of mine, but he is related. This descendant noted a family story (which she expressed skepticism about) that Nicholas Ickes had been a right hand man to George Washington and had looked between the logs of the General’s cabin to see him kneeling in prayer before a battle.

…Who Only Served Two Months!

This is, of course, a spectacular story. Another family member, however, replied to this message less than a month later. Quoting from Ickes’s pension application, she noted that in September 1781, he enlisted in the Continental Army as a substitute for a man named George Evans and marched from Philadelphia County (where he then resided) to Uniontown in Bucks County, Pennsylvania where he was stationed in the garrison and served about two months. His pension application was, in fact, rejected because he did not serve six months.

Clearly the contrast between tradition and documentation here could not be much more stark. The idea that a private who served in the Continental Army for two months became a right hand man to George Washington screams exaggeration. In fact, at the time Nicholas Ickes enlisted in Pennsylvania, Washington was in Yorktown, Virginia, preparing for the siege that became the climactic battle of the war. While Washington did spend the winter of 1781-1782 in Philadelphia, dealing with administrative matters relating to the Continental Army, he was not with the army and so the chances that Nicholas Ickes personally encountered him are virtually nil – and he certainly did not cross the General’s path just before a battle. The original poster followed up with a less dramatic version of the original story – a tradition that Nicholas Ickes, while on duty near Washington’s headquarters at Valley Forge, peeped through an opening between the boards and saw the General alone on his knees in prayer. This story, while omitting the tradition that Ickes had been a right hand man to Washington, is no more believable. The Continental Army spent the winter of 1777-1778 at Valley Forge and Nicholas Ickes did not enlist until September 1781.”

Editor’s Note: Confounding stories of military forebears illustrates just one way genealogists can be lead down the primrose path in their research. Mr. Hite’s acclaimed new book, Sustainable Genealogy: Separating Fact from Fiction in Family Legends is full of such cautionary tales. You can learn more about it by clicking the button below.