By Carolyn L. Barkley

When I first began to attend genealogical conferences, I heard a speaker from the North Carolina State Archives say, “When I hear someone ask for marriage records or wills, I know that the individual is a genealogist; when I hear someone ask for land records, I know that the individual is a researcher.” That quote has resonated throughout my own research ever since.

I set myself a goal of reading all the Barkley deeds in the Northampton County Court House in Jackson, North Carolina (a job, I should admit, that isn’t complete yet). Very quickly, I discovered the value of taking on this type of comprehensive study. My research focused on the family of George Barkley who had migrated to Northampton County from Isle of Wight County, Virginia, sometime in the late 1760s. George’s son Rhodes had twelve children during the span of two marriages. I knew nothing more than the name of one of his sons, William Barkley. However, in transcribing the Barkley index entries from the deed indices, I found a deed dated 27 January 1818 for a William Barkley (grantor) and Rhoades [sic] Barkley (grantee). I immediately checked the recorded deed and experienced one of those golden moments of genealogical research. In this will, William Barkley of Sumter District, South Carolina, had returned to Northampton County to deed to “my father Rhoades Barkley of Northampton County, North Carolina…all my right, title, interest, and claim in a certain tract of land lying in County, on the north side of Wiccany swamp, being the land enured by Richard Allen Senr Patent granted him, and I the said Wm Barkly do for myself, my heirs jointly relinquish, warrant and ever defend my said wright unto him the said Rhoads Barkly…” I knew that Rhodes Barkley’s first wife had been Allice [sic] Allen, so William was probably talking about his grandfather, Richard Allen. From this one deed, I learned the residence of William at the time, learned that he may well have been a son of Rhodes’ first marriage, and opened an entirely new line of research on this Barkley family, this time in South Carolina. I was hooked on land research!

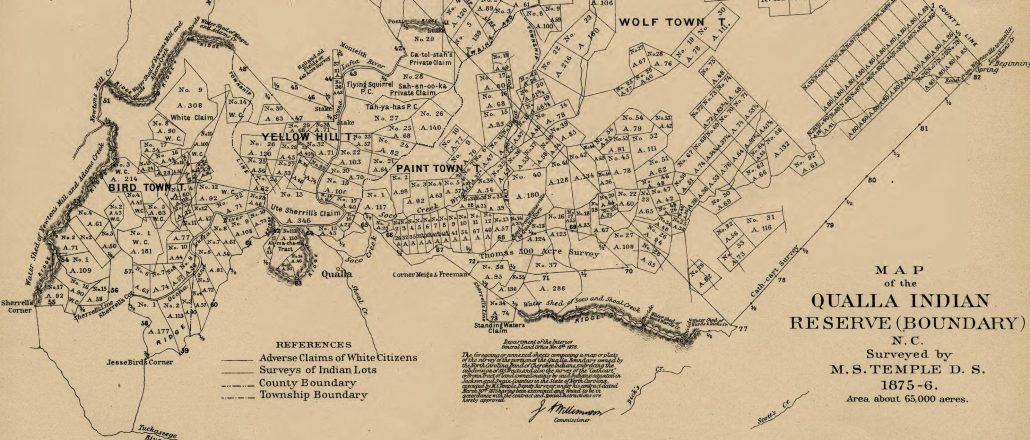

As researchers, it is important for all of us to learn more about land development in order to better understand land records and their contents. Land was not developed uniformly during the colonial period. In New England, townships were the predominant form of development. First the general court of the colony would grant approval for a new township, usually about six miles square in size, and then proprietors of that township would assign the land to specific inhabitants. One of the strengths of New England land records is the existence of landowner, or plat maps, dating from very early in a locality’s development. In the southern states, land development was quite different. Colonists asserted their individual choices in selecting property in a system originally driven by the head right system that granted individuals fifty acres for every individual (head) brought into the colony. This method was not one of controlled settlement, formal surveying was seldom done prior to settlement, and boundaries were often self-described. For the most part, southern property was not laid out around a town center, but rather was clustered around transportation routes – rivers, streams, and the coastline.

Lands that were controlled and granted first by foreign governments, and then by colonial or state governments, are known as “state-land states.” These states include Connecticut, Delaware, Georgia, Hawaii, Kentucky, Maine, Maryland, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, New Jersey, New York, North Carolina, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, South Carolina, Tennessee, Texas, Vermont, Virginia (and later West Virginia). The most common surveying method for state-land states is the “metes and bounds” system that describes markers, measurement, and directions for each piece of property. A metes and bounds survey starts with a designated marker (tree, stone, road, etc.) and then proceeds through a series of straight lines (or geographical boundaries of the course of a stream, creek, swamp, etc.) from point to point until it returns to the starting place. Each “course” or line is described by the name of the land owner whose property shares that line or the water course it borders; each corner may be described by another designated marker. Finally, each segment of the description also indicates direction (north, south, east or west), degrees (compass direction between 0º and 90º) and distance, measured in rods, poles, perches, chains, and links). Tables help convert these surveying measurements into actual lengths: 1 chain = 66 feet, 1 link = 7.92 inches; 1 rod/pole/perch = 16.5 feet. One mile equals 80 chains or 320 rods/poles/perches.

The land records in states that were initially controlled and dispersed by the United States government are completely different. These federal-land states include Alabama, Alaska, Arizona, Arkansas, California, Colorado, Florida, Idaho, Illinois, Indiana, Iowa, Kansas, Louisiana, Michigan, Minnesota, Mississippi, Missouri, Montana, Nebraska, Nevada, New Mexico, North Dakota, Ohio, Oklahoma, Oregon, South Dakota, Utah, Washington, Wisconsin and Wyoming. Federal-land records comprised the largest single-subject group of records until the advent of twentieth-century records, and include a wide variety of types of records such as homesteads, military bounty lands, mining claims, and agricultural and timber management. They are very rich in genealogical information. These lands were first granted to individuals in 1785, with the first land office opening as early as 1797. The original intent was to raise revenues to compensate for the costs of the Revolutionary War; to grant lands (rather than financial payments) to soldiers; and to sustain burgeoning migration to the west. These land transactions were not described by metes and bounds, but instead were surveys based on meridians.

A meridian is an imaginary line running north to south, from pole to pole; base lines are horizontal lines running east and west that intersect the meridian line. (A map of meridian and base lines can be found at the Bureau of Land Management’s website.) Distance to the east or west is measured from a specific meridian. The meridian region is divided into no more than eight tracts, each twenty-four miles square. Each tract is then divided into sixteen townships, each approximately six miles square. Imaginary lines called ranges run north to south six miles apart, the width of the township. Each township is divided into sections one mile square and containing approximately 640 acres. Each section is numbered beginning in the northeast corner and counting westward. If you have ever flown over the mid-west and looked down on the landscape, the land divisions are seen easily. Sound confusing? You may want to read “Graphical Display of the Federal Township and Range System” or “Range Maps for Dummies” web pages to obtain more of the details involved in this system. The first article discusses the system in general; the second focuses on Illinois land descriptions. Both provide clear, informative descriptions.

A variety of print resources are also available to assist you in your understanding of land development and description. I highly recommend the following two titles if you want to understand more of the basics: Land and Property Research in the United States by E. Wade Hone (Ancestry 1997) and Dividing the Land: Early American Beginnings of Our Private Property Mosaic by Edward T. Price (University of Chicago, 1995). Both will give you a clear understanding of the history of land transactions as well as the specifics of the two systems of land descriptions discussed in this article. In addition, check for printed compilations of land records specific to a state or locality. A good example of a state-specific resource is found in the three volumes of Ohio records by Ellen T. and David A. Berry (Early Ohio Settlers, Purchasers of Land in Southeastern Ohio, 1800-1840; Early Ohio Settlers, Purchasers of Land in East and East Central Ohio, 1800-1840; and Early Ohio Settlers, Purchasers of Land in Southwestern Ohio, 1800-1840) and in Albion M. Dyers’ First Ownership of Ohio Lands, all published by Genealogical Publishing Company. These titles are also available in a CD entitled Ohio Land and Tax Records. The CD also includes Early Ohio Tax Records by Esther Weygandt Powell and is available from GPC.

Several resources are available if you are interested in searching original records. The four-volume Federal Land Series by Clifford Neal Smith (Clearfield, 1972, reprinted 2007) contains a “calendar of archival materials on the land patents issued by the United States Government, with subject, tract, and name indexes.” The focus is on land patents, the first transfer of land to individuals by the government and by Virginia during the period 1788 to 1835. The best resource online is the Bureau of Land Management’s Official Federal Land Records Site that “provides live access to federal land conveyance records for the public-land states” as well as images for more than three million land title records issued between 1820 and 1908 for eastern public-land states. New additions to the site include survey plats and field notes. Select the tab for land patent searches in the upper navigation bar. The basic search tab will allow you to search for an individual or a surname within a specific state. Searching for land patents for any Barkley in Alabama, for example, I found 38 entries. For each entry, I had access to a patent description, a legal land description (here’s why you need to understand how to read a land description), a document image (GIF, PDF or TIFF options are provided), as well as the ability to order a certified copy of the document. If you want to search all states, you must choose the standard search tab rather than the basic. A search for all Barkley patents in all states yielded seventeen pages of hits. Be aware that the “all states” choice is at the end of the list of state names in the drop-down box. In order to search the original surveys, you must have a specific land description to enter into the search form. You should also check Arphax Publishing Company’s family maps land patent books. These books include “county by county, state by state [maps] for original settlers whose purchases are indexed either in the U. S. Bureau of Land Management database or the Texas General Land Office database” and are available for Alabama, Arkansas, Colorado, Florida, Idaho, Iowa, Illinois, Indiana, Louisiana, Michigan, Minnesota, Mississippi, Missouri, Nebraska, New Mexico, Ohio, Oklahoma, Texas, Utah and Wisconsin. Check for the availability of your county, as all counties may not have been completed yet for all states. These books provide surname indices and maps that allow you to locate your ancestor’s federal or Texas land purchase (first-land-owners), as well as their neighbors and the history of settlement of the particular area. The web site also offers you the ability to look at samples of their products.

Knowing how to draw a plat from its description is a great way to enhance your understanding. Plan to attend a land platting workshop offered either in your area, at a national conference, or as part of an institute such as the Institute of Genealogy and Historical Research held at Samford University in Alabama each June. At the latter, an entire week’s course covers land platting in depth, including both metes and bounds and range systems. (This course is not given every year, so check the course offerings.). Deed Platter is an online application to help you plat your deed. In addition, software programs such as Deedmapper will provide you with the tools to create plats, join plats together into neighborhoods, and then export them to Google Earth or superimpose them on a USGS topographic map.

To me, land records are one of the most important resources in genealogical research. Being able to put your ancestor’s feet on the ground in a specific place, at a specific time, with specific neighbors is the key to an enriched understanding of the life he or she led and the neighbors who shared that same place and time.

Happy research and platting.